The first exhibition of 2021 at Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank is a joint project. “WIR. Nähe und Distanz – Jubiläumsausstellung mit Werken aus der Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank” is marked by four jubilees: the Kunstforum and the art collection turn 35 years old, Werkstatt für Kreative was founded 15 years ago and last but not least Berliner Volksbank celebrates its 75th anniversary. Commemorating these occasions, fourteen employees of Berliner Volksbank eG co-curated the exhibition together with the two art-historians from Stiftung KUNSTFORUM.

Balancing closeness and distance creates a new kind of community. Absence and presence, distance and attraction generate a diverse interplay.

In terms of content, the exhibition is on the one hand about the personal perspective of the guest curators. On the other hand, historical and current issues, different perspectives on the city and society come into focus. As a result, the exhibition shows the diversity of the collection.

On view are works from the art collection of Berliner Volksbank including artworks created by: Hermann Albert, Gerhard Altenbourg, Rolf Biebl, Christa Dichgans, Klaus Fußmann, Sylvia Hagen, Angela Hampel, Werner Heldt, Thomas Hornemann, Ingeborg Hunzinger, Karl-Ludwig Lange, Wolfgang Leber, Markus Lüpertz, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Harald Metzkes, Silke Miche, Kurt Mühlenhaupt, Roland Nicolaus, Wolfgang Peuker, Erich Fritz Reuter, Cornelia Schleime, Ludwig Gabriel Schreiber, Ruth Tesmar, Christian Thoelke, Hans Uhlmann and Ulla Walter.

A catalogue has been published for the exhibition and is available for purchase here: [Publications]

Catalogue text by co-curator, Dr Janina Dahlmanns

The year 2020 was marked by the pandemic – and the question of proximity and distance left its mark on people’s everyday lives, as well as on the work of the Berliner Volksbank curatorial team. Could we still provide safety with a physical distance of 1.5 metres? Was there closeness and a shared sense of “we” even in the virtual space of the video conference? Or more generally: does solidarity and community grow even / despite / because of spatial distance?

As topical as these questions were, there were also fundamental, philosophical thoughts on this subject. The parable “Die Stachelschweine” by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, created in 1851, already addresses the dilemma of closeness and distance in coexistence: a group of porcupines has the need for physical warmth – at the same time, however, the neighbour’s quills hurt the closer the individuals get to each other. It is therefore necessary to find the ideal distance in order to use the communal warmth without getting pricked by the other’s quills. This conflict can be transferred to humans. On the one hand, there is the strong human need for closeness, for solidarity and community, for friendship and love. On the other hand, people also strive for individualism and self-determination – some have a need for peace and solitude.

In this field of tension between closeness and distance, it is important to find a balance. The challenges lie in the personal sphere, in the shaping of private relationships of all kinds: from love to friendship and family, to everyday encounters with others.

Living conditions in a big city, like Berlin, tests the ability for each individual to find his or her way in the hustle and bustle of anonymous crowds. At the same time, it is precisely the crowd of different people that makes the city so fascinating and lively. Community, cohesion and pleasure are contrasted with loneliness, isolation and forlornness.

The relationship between the individual and society, to the political situation and to history, can also be considered in terms of proximity and distance. It is a question of how strongly the individual allows his or her actions to be influenced by the social environment and, at the same time, how historical developments guide personal actions and feelings.

These questions are a source of constant new debates, considerations and reflections in order to determine and define one’s own position. It is precisely with the means of art that the complexity of positive and negative emotions and needs can be depicted.

The Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank focuses on figurative art, so unsurprisingly the image of the human being is strongly represented. Thus, the emotional state of man and the numerous related issues of man as well as the individual within society often become the subject of our art. The environment of the human being, the concrete, the metaphorical or the emotional space, also is repeatedly found in these works of art. Thus, it made sense to select works which included the idea of ‘proximity and distance’ and to approach it with a variety of artistic positions.

Artistic self-portraits

The main subject of the exhibition, Klaus Fußmann’s “Atelier mit roter Jacke,” sets the tone for the overall theme: Distance is created by initially missing the presence of a human being. At first glance, this distance is unsettling. However, what the depiction displays forcefully is the artist’s personality. Although he has left his studio, the objects in the room, such as paint tubes and pots, demonstrate activity. The white wall stands for the space to be filled with art. The signal red jacket echoes the creative energy of the artist.

In contrast, Christa Dichgans uses countless small figures in “Begegnung mit den Ichs” to illustrate the many facets of her identity. In the foreground, she herself is seen painting an angel figure, which can be understood as a symbol of the departure and free creativity of artistic creation.

In Wolfgang Mattheuer’s “Selbstbildnis,” the artist shows himself with a brush in his hand as a “Bild im Bild”(picture in a picture) in the form of a portrait on an easel. Through the open windows and the reflections of the cityscape, Mattheuer opens up the studio space and refers to his surroundings: he allows the world from outside to permeate into his interior and thematises the interrelation in art, mirrored and transformed many times over. The complex process of stepping back to artistically survey the truth and at the same time reproduce it in detail is indicated by the interweaving of the two spaces.

Loneliness

Mattheuer’s “Blinder Mann” leads the viewer into a group of works dealing with human loneliness. The monochrome painted figure appears petrified and sits without any connection to its environment in front of a dark background. The blindness illustrated by the closed eyes prevents contact with the surroundings.

This impossibility of connection is also shown in Ingeborg Hunzinger’s marble sculpture “Über die Schulter.” The block-like form of the figure prevents any interaction with the surrounding space; it is entirely focused on itself. She appears completely alone and left to her own devices. In her isolation, she is completely on her own. But the effect also varies: possibly the figure also protects itself from its environment, withdraws voluntarily and deliberately does not allow its surroundings to get close to it.

The figures in Wolfgang Leber’s “Auf der Galerie” also move in isolation in a convoluted space, possibly a situation in a railway station or a shopping centre. The figures do not look at each other and their paths do not cross either, an encounter does not seem possible.

Karl-Ludwig Lange’s “Fast im Warmen” further increases the isolation of the individual. The shadowy, frontal figure faces the viewer directly – but the blurring of the details and the cloudy colour scheme convey a concrete as well as metaphorical distance.

Love

The juxtaposition of the need for closeness and distance is a recurring theme in the representation of love in art. In Ruth Tesmar’s “Unter Wasser – Schweben,” the silhouettes of a woman and a man move as if weightless in a blue room. Their bodies float next to each other and fit into each other’s forms, yet they do not touch. In this poetic image, water can be understood as a metaphor for life: The couple floats through close to each other and each remains autonomous.

Hans Uhlmann’s bronze “Weibliche Gruppe” shows a touching image of physical intimacy. The formally minimalist bodies are drawn in a common outline, their arms resting on each other’s bodies, while their heads virtually merge.

Angela Hampel’s lithograph “Dich spüren will ich…” (I want to feel you), on the other hand, speaks of the longing for this physical contact, as the title suggests. The female figure illustrates the conflict of this desire. The figure with a piercing gaze puts her arm around her own shoulder as if she wants to embrace herself. In the other hand, she holds a serpentine animal, although it remains open whether it is being warded off or drawn towards her. The bald head refers to the feeling of defenselessness and vulnerability.

Ambivalent emotions are also the theme of Hermann Albert’s painting “Sich kämmender Akt”. A naked woman seems to feel unobserved in her room. But a shadow on the wall reveals a male observer. The threatening aspect of desire and love is illustrated. At the same time, the scene is also a statement on the subject of voyeurism in male-dominated art, in which the long artistic tradition of depictions of female nudity manifests itself.

Encounters

At first glance, Markus Lüpertz’s painting “Zwei Krieger” appears threatening. Two figures with archaic shields, sword and lance meet each other aggressively. Their faces, however, are covered with masks that appear rather amicable and open. The scene thus conveys an impression of the diversity of male adversaries, oscillating between curiosity and aggressiveness.

The bronze sculpture “Wanderer namenlos” by Sylvia Hagen presents three sketchily modelled figures. The main focus is on the stances of the bodies, which are turned towards or away from each other. The interplay of closeness and distance is inscribed in the “wanderers” on the path of life.

Gerhard Altenbourg’s woodcuts work with the serial reproduction of a figure that is always the same. Lined up one after the other, they convey the uniformity of the anonymous mass of people. At the same time, the colourful design and the printed grain of the wood give rise to reflection on the simultaneous uniqueness of the individual.

Altenbourg’s filigree drawing “Flug” shows a single being, a mythical-mystical figure with wings, separated from its surroundings by the ability to fly. The head turned with a gentle smile, however, seems to indicate the existence of others.

Life in the city

Among the early works from the collection are Werner Heldt’s charcoal drawings from Berlin. Here he observes scenes from post-war everyday city life, depicting gatherings of people as they often occurred in urban life at the end of the 1940s. In these depictions, the individual formally merges with the mass.

In Thomas Hornemann’s “Cabaret la Marina” and Kurt Mühlenhaupt’s “Sommerlicher Badestrand”, the cheerful side of city life is illuminated. People get close to each other during leisure activities ranging from dancing in the pub to sunbathing, bathing and playing on the beach.

The confusion of the big city is the theme of Ulla Walter’s work “U-Bahn”. The human figures are dissolved into abstracted forms, yet the feeling of crowdedness, confusion and density is visible. The individual does not appear on the train, but is lost in the tangle of the masses.

Silke Miche’s “Kästen” does not show people themselves, but their urban living situation. In the seemingly endless row of balconies, the conformity and narrowness of urban living space becomes clear. The bright colours, however, dissolve the oppressiveness and hint at the individuality of the residents.

A look back

With the political turnaround after 1989, a fundamental political and social change occurred in German history, which found artistic expression in subtle ways.

In the painting “Sibirischer Frühling,” Cornelia Schleime illuminated her personal situation when she left for West Germany in 1984 after great pressure from the GDR authorities. The painting shows a snow-covered landscape, a distant “Siberia” from which she was now able to distance herself. The colourful dots as well as the “Frühling” (spring) implied in the title symbolise her optimistic mood of departure.

Wolfgang Peuker’s 1990 painting “Pariser Platz II” is quite different. A leaden grey impenetrability dominates around the Brandenburg Gate. Although the gate has been opened by the fall of the Wall, the world beyond the gate seems infinitely distant. One intuitively tries to avoid an encounter with the eerie dark figures that come from there.

Harald Metzke’s “Blinde Kuh” is also ambivalent, a painting that at first glance seems to be depicting a cheerful party game. Yet, as is so often the case with Metzke, the painting can also be understood as a metaphor for social interaction. The blindfolded woman is trying to touch the other people. She is trying to make contact with them. If one considers the genesis of the work in the German post-reunification period, it could also be a commentary on the encounter between East and West Germans. The not-seeing with blindfolded eyes is symbolic of the not-knowing and not-understanding in the attempt to come together – and the evasive fellow players also underline the failure of the encounter.

Janina Dahlmanns

The presentation at the Kunstforum der Berliner Volksbank showed how the 1920s era has influenced the artistic work of later generations up to the present day.

The 1920s still fascinate people a hundred years after this exciting epoch. This is reflected in the success of series such as “Babylon Berlin,” but also impressively in the fields of design, modern literature and current fashion.

Art reacted to the 1920s in its own time with styles such as New Objectivity and Magic Realism. The exhibition “Die wilden 20er – Nach(t)leben einer Epoche.” (The Wild Twenties – The Afterlife of an Era) shows the extent to which later generations of artists were inspired by these styles and still are today. The exhibition shows works by Gudrun Brüne, Albrecht Gehse, Hubertus Giebe, Otto Gleichmann, Clemens Gröszer, Karl Lagerfeld, Hartmut Neumann, Roland Nicolaus, Wolfgang Peuker, Bernard Schultze, Volker Stelzmann, Christian Thoelke and Britta von Willert are presented.

The artworks were created from the 1970s to the present. They bear witness to how influential this epoch was in terms of style, and that later generations of artists also made reference to the clear, austere representationalism of New Objectivity and the surreal and alienated scenes of Magic Realism.

A catalogue has been published to accompany the exhibition and is available for purchase: Publications

Catalogue text by curator Dr. Janina Dahlmanns

The Berliner Volksbank art collection focuses on representational art, which was mainly created in Berlin and the surrounding regions after 1945. The collection, therefore, contains the most diverse range of positions in German modernist art, from expressive forms of expression to old-masterly realist painting to strikingly reduced viewpoints. One group of works stands out for its precise, almost emphatically realistic painting style as well as its naturalistic rendering of colours, volumes and perspective. At the same time, they show alienating effects such as lighting conditions reminiscent of nocturnal visions or dreams, or exaggeratedly dramatic gestures. Some paintings are permeated by a mysterious atmosphere and encourage the viewer to consider the particular mood in each case.

The earliest paintings of this kind from the Berliner Volksbank art collection were created in the 1970s, such as “Nachtcafé” by Hubertus Giebe. A whole series, on the other hand, dates from the last 20 years, such as the works by Clemens Gröszer, Volker Stelzmann, Wolfgang Peuker or Gudrun Brüne. The painting style of these artists is reminiscent of the overly precise style of verism of the 1920s.

During the Weimar Republic, currents that were more strongly oriented towards seen reality, such as Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) or Magical Realism, became increasingly prevalent in German art. After modernism had broken with traditional forms of representation around 1900 – Impressionism with the idea of uniform light, Expressionism with naturalistic colouring or Cubism with classical perspective – a “return to order” was evident in art throughout Europe. After the horrors of the First World War, artists in Germany strove for a new objectivity and an unsparing depiction of what they saw. The uncovering and criticism of social ills and societal ambivalences were to be visualised in this way. Other artists painted scenes that only appeared realistic at first glance, but on closer inspection revealed breaks with familiar reality and made the uncertainties of the social situation visible. A lively and thoroughly diverse art scene illustrated the 1920s. From the boisterous celebrations of the bohemians in the cities and their dance on the volcano to the new understanding of the role of the modern woman to the enormous social problems and the gap between rich and poor, everything was thematised. This short era came to a brutal end when the National Socialists came to power in 1933, bringing this cultural flowering to an abrupt end.

The question arises as to why artists such as Clemens Gröszer, Volker Stelzmann, Hubertus Giebe, Wolfgang Peuker or Gudrun Brüne reacted so forcefully to the style and themes of this period many decades later.

By the mid-1960s, a first renaissance of the visual language of the 1920s had already emerged in the eastern part of Germany. At the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig, a figurative art movement emerged that broke through the narrow guidelines of the “Socialist Realism” prescribed by the state and revived the painterly, technical refinements of various art historical models. The so-called “Leipzig School,” still famous today, was born. Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer and Bernhard Heisig also took their cue from greats of the 1920s such as Otto Dix, Giorgio de Chirico, Oskar Kokoschka and Max Beckmann. In Tübke’s work, the examination of older art, especially Renaissance and Mannerism, played a major role. The artists of the 1920s had already turned this gaze to the past. In a sense, one can speak stylistically and technically of the renaissance of a renaissance, which was, however, thematically related in each case to the current present. The art of the “Leipzig School” established itself through its three main protagonists and was carried on and developed by its numerous students at the Leipzig Hochschule. Two stylistic currents dominated: painting in a veristic, precise glaze technique and painting in a gestural, impulsively designed pastosity.

In the 1970s, Giebe, Stelzmann and Peuker studied at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst. They found models for their own artistic work in the examination of Otto Dixs’ work, but also of Giorgio de Chirico, a representative of the Italian Pittura Metafisica, which developed parallel to Magical Realism in Germany. For Giebe, Max Beckmann was an exciting inspiration, Stelzmann dealt with even older masters of art history such as El Greco or Pontormo, while Peuker developed his own variety of Magic Realism. Each of the artists thus arrived at a very personal style.

Thus the art of the Leipzigers succeeded in the balancing act of, on the one hand, ostensibly conforming to the desired line of GDR art policy, setting itself apart from the West through representationalism, and thus enabling itself to work artistically in a more or less undisturbed manner – on the other hand, possibilities opened up for making its own and independent pictorial statements, precisely through alienation and profundity. Thus, the direction of Magic Realism, which originated in the 1920s, offered many artists in the GDR an approach of using enigmatic elements and numerous layers of meaning to refer to the pictorial statement that was actually relevant to the artist – only that this was not apparent at a superficial glance.

Common characteristics of the artists such as Giebe, Stelzmann and Peuker are the precise lines, the attention to detail and the finely glazed layers of paint as well as the surreal and magically charged subjects. Moreover, they have maintained their respective individual styles even during the Wende and post-Wende periods. It seems that the visual language they found was suitable for vividly depicting their own feelings even in the face of social and personal changes.

Other examples of artists who transferred this style of painting, which borrowed from the art of the 1920s, into their handwriting are Gudrun Brüne, who trained in Leipzig and then worked as a lecturer at Burg Giebichenstein in Halle, and the two Berlin painters Clemens Gröszer and Roland Nicolaus.

Gröszer often created complex narratives with his works, using multi-layered references from all eras to create a conundrum of human longings, dreams, hopes and expectations. He incorporated allegories and symbols into his works, interweaving the worlds of dream and fantasy with elements from his everyday life. Thus his figures, who reside in mysterious shadow worlds, are dressed in the chic of the contemporary underground scene, while a masked magician may be standing next to the S-Bahn station at Berlin’s Alexanderplatz. Gröszer transposes an ancient way of painting into his present, while the technical perfection of painting was also always a major concern.

“Early on, Gröszer belonged to the group of painters who attempted to rescue genuine painterly ideas from the ingredients of the crisis, the loss of autonomy, media competition and the new, commercially determined cultural sign system, so to speak.” (Matthias Flügge, in cat. Gröszer – Antlitz, 2012, p. 11)

Gudrun Brüne’s work also focused on painterly precision, while at the same time her work is permeated with symbols and allegories of human existence. Her work often mixes genres: Portraits are combined with still lifes and figures enter into silent dialogues with things. Dream and memory images are merged with real scenes from Bruene’s studio. The objects, such as dolls, masks, mementoes, play a symbolic role that underlines the overall effect: the outside world is reflected in the inside world of the studio.

Roland Nicolaus deals with the 1920s in a special way. In his most recent works, he combines various painterly styles, from meticulous detail painting to bold Pop Art, and creates collage-like panoramas. This is also a conscious reference to the 1920s since the principle of collage first emerged in this period with the Dada movement. In these painted collages, sometimes supplemented by pasted-in evidence of everyday culture, Nicolaus picks up on figures, observations and phenomena of social reality in Berlin in the 21st century and presents a moral image of the present. Through quotations from art history in constellations and figures, he reveals distortions and absurdities of the social reality of the present, in which he certainly sees parallels to the 1920s in Germany in terms of content. The result is a bitterly wicked commentary on the present situation.

This magical-surreal direction in the art of the late 20th century, which forms a significant part of representational art in Germany, does not, however, find an endpoint with the generation of artists trained in the GDR. The fascination with painterly accuracy, the detailed formulation of the superficially visible in connection with subtly hidden levels of meaning is continued into the present by younger generations of artists.

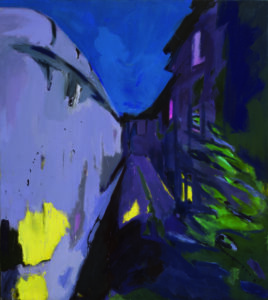

Britta von Willert, for example, who trained in the early 2000s, has also opted for representational painting, modelling figures and spaces with realistic precision. At times, she incorporates conceptual images into the depictions and shows an openly conceived tradition of the magical-surreal, as in her series of Berlin paintings, which make the place’s known past visible in figures taken from historical black-and-white photographs of the early 20th century and create suspenseful cross-fades. In other works from Berlin’s nightlife, the quiet atmosphere and introverted figures recall the depictions of the American painter Edward Hopper. In the 1920s and 1930s, Hopper visualised the loneliness of modern man and the alienation of city life.

Depicting the social issues of the present in the relationship to human emotions is also the aim of Christian Thoelke, who studied in the years before and after the turn of the millennium. His paintings are dominated by what at first sight appears to be a calm mood, but on closer inspection is also perceived as latently sinister and charged with tension. It is about universal questions of man in relation to upheavals, uprooting, transitions, fears and longings. The social themes are not depicted narratively but made visible in their essence and core. The painterly sharpness of detail and precision in Thoelke’s painting is reminiscent of New Objectivity – but it also betrays the inspiration and stimulation of his teachers Wolfgang Peuker and Ulrich Hachulla, both of whom carried on the technical care of the “Leipzig School.”

The art of the 1920s thus continues to have an effect today and inspires generations of artists. Their approach and style offer a possibility to transfer the questions and observations of one’s own reality of life to art, independent of contemporary styles and fashions. The accuracy of the technical realisation goes beyond subjective ego-feeling and the expression of personal sensitivities. The precise description of things as well as the mysterious enigma and great atmospheric tension make it possible to visualise thoughts on the social situation without appearing narrational and striking. Instead, the viewer’s thought process is stimulated in a subtle way and his attention is challenged for nuances and intermediate tones. This is what makes this style of figurative art so appealing and fascinating, a style that, in a way, is timeless and endures into the Post-Post-Modern era.

Janina Dahlmanns

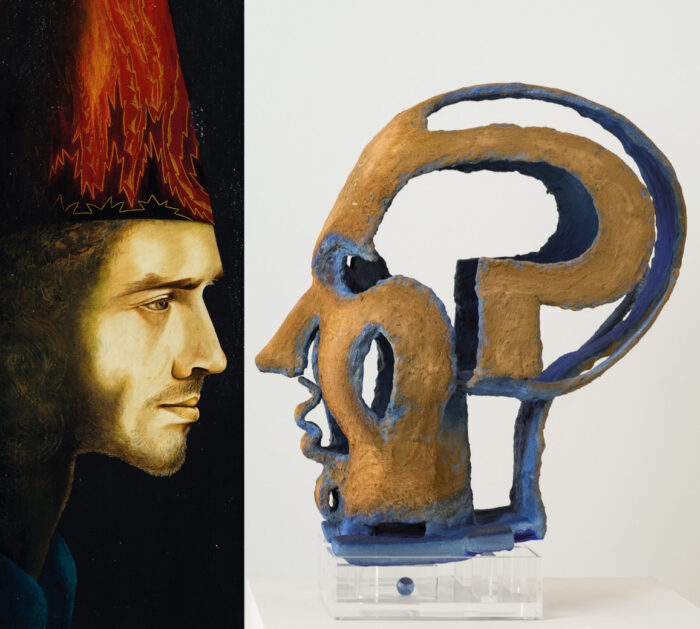

In the exhibition “Tête-à-Tête. Köpfe aus der Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank,” visitors to the Kunstforum in Charlottenburg will encounter one of the most interesting series of works from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank: head representations. They are outstanding ambassadors for the collection, specialising in figurative art. The works of 22 artists, who mainly live in Berlin and Brandenburg, show the diversity of topics with examples from almost seven decades from 1950 to 2018. Since the modern era, artists have dealt more and more freely with the subject of “head representations,” detaching themselves from the classic portrait and creating fascinating interpretations. In the exhibition, form and expression are particularly in dialogue with material and technology.

Designed using concrete, glass, steel, cast stone and terracotta, the sculptural works by Horst Antes, Clemens Gröszer, Dieter Hacker, Christina Renker, Gerd Sonntag and Ulla Walter should be mentioned. The exhibition also includes diverse paintings, drawings and works on paper and graphics from important artists of the collection such as Gerhard Altenbourg, Luciano Castelli, Christa Dichgans, Rainer Fetting, Dieter Hacker, Angela Hampel, Martin Heinig, Burkhard Held, Helge Leiberg, Markus Lüpertz, Helmut Middendorf, Roland Nicolaus, AR Penck, Hans Scheuerecker, Erika Stürmer – Alex, Max Uhlig and Dieter Zimmermann.

Introduction to the exhibition “Tête-à-Tête. Köpfe aus der Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank” by curator Dr. Dörte Döhl

When it comes to the subject of the head in art, one first thinks of the traditional genre of the portrait. The art of portraits usually emphasised the individual’s personality, and these commissioned works were mostly created with the intention of self-portrayal or the staging of power. It is not uncommon to use the portrait as a fascinating documentation of history and cultural history. In modern occidental art of the 20th century, however, we often encounter head motifs that put the individual aside and instead, underline other aspects of being human or reinterpret physiognomy. It is not a matter of classical representation, but of recording emotions and experiences or states and perceptions.

Today’s artists can look back on around a century of development that has fundamentally expanded the way we view the human head. At the end of the 19th century, Edvard Munch, in his composition known as “The Scream,” used simple stylistic means to make the motion of fear tangible, especially in the face of his figure. A short period after the turn of the century, Pablo Picasso began to develop a new visual language. Inspired by African sculpture, he also changed the human figure by breaking open forms. Cubism focused on an object from several perspectives at one time and thus also changed the perspective of the human head in art.

This turn to abstraction was further developed in the 1920s by Paul Klee and Alexej von Jawlensky. Klee’s well-known painting “Senecio” shows a round face painted in a few strong colours. Here too the influence of African mask art is to be highlighted, but above all, the geometric design with square, triangle and circle demonstrates the strong influence of the Bauhaus, at which Klee taught. Jawlensky, who, like Klee, came from the circle of the artist group “Blauer Reiter,” proceeded more systematically. He dissolved the shape of the face into a pattern of lines and colours. Not only that, but he also created several series in which he systematically explored the subject. The “Mystical Heads” were the first to emerge, then the “Saviour heads” and finally he himself spoke of his “abstract heads”. Immersed in themselves, the faces radiate a spirituality that has its roots in religious art. The images look like new creations in the spirit of the Orthodox icons. Picasso’s “Weeping Woman” created in 1937 has become an icon of modern art. As a mirror of strong emotions, the sitter’s face shows pain in a haunting way. Created as a result of the war painting “Guernica”, the tragedy of the epoch is expressively captured in the form of Dora Maar’s partner.

The Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank comprises an extensive inventory of head depictions, of which only a selection can be shown in the exhibition “Tête-à-Tête.” The installations date from 1950 to 2018 and therefore span almost seven decades. Since “images of people” is a motto of the figurative collection, heads are an important subject matter among the works of art that have been collected over the last three decades.

The new figuration in the 1960s is represented by the steel head of Horst Antes, who became famous in particular with this type of representation or through the so-called “cephalopods.” His compact profiles explore the universal form of the subject treated in all cultures. Thus, the “head with standing figure, hoop and staff” also seems like an archaic symbol.

In contrast, Gerhard Alternbourg created filigree faces in countless works on paper. There are outstanding examples of this in the art collection the Berliner Volksbank. His “head” from 1971 confronts the viewer with a furrowed facial landscape in which memory is carved and at the same time transience is inscribed. Hans Scheuerecker devoted himself to the topic in a similarly intensive manner. The expressiveness of the line stands out in his “faces,” which playfully deal with elements of abstraction.

Outlines are often sufficient to associate a head shape, which Helge Leiberg also makes use of in “Wildheit im Kopf.” By “blending” the face with the figure of a female dancer, inside and outside views merge into one vision. While an emotional state is described here, in Ulla Walter’ “free thinker with an Archimedean point” openness in all directions is an expression of an attitude of mind. The hollow shape of the head embodies the opening to the outside and the absorption inward in thinking. A process that has to be explored again and again. Flowing transitions and openness are also themes in Gerd Sonntag’s glass sculptures. He has developed new techniques for his heads, which are made of several layers. The transparency of materials gives them a luminosity that at the same time causes the closed form to dissolve into light and colour.

The subject of contemplation is embodied by the thoughtful “astrologer” Markus Lüpertz, who seems to be a mediator between different worlds. The idealised head of Clemens Gröszer, which stands in the tradition of supersensible angel figures, also alludes to the earthly.

The powerful expression of Berlin’s “Neue Wilden” is dominant in Luciano Castelli’s monumental “Chinese Portrait” and Helmut Middendorf’s “Great City Head” from the 1980s. They are captured as free interpreted contemporary heads.

The subject of Rainer Fetting’s impressions of New York are men with hats. The big city encounters leaving fleeting impressions. With the hat as an accessory, the artist uses his possibilities as a director of the picture series.

Angela Hampel and Roland Nicolaus take up the fact that headgear or masks are traditionally used to stage a head. In their paintings “Selbst mit Maske” and “Selbstbildnis” they simultaneously pose the question of one’s own identity. Christa Dichgans shows her self-image in a sea of heads. In view of the diversity of being, she emphasises the necessity of the individual’s self-determination.

Dörte Döhl

A catalogue has been published to accompany the exhibition. This can be purchased for 5 euros plus shipping costs. If this should interest you, please send an email to:kunstforum@berliner-volksbank.de

22 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH.

The exhibition “ZEITENWENDE – 30 Jahre Mauerfall. Werke aus der Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank” takes the 30th anniversary since the fall of the Berlin Wall as an opportunity to show paintings from the time of the division of Germany and the political upheaval in the GDR. In this exhibition, the artworks lead you to question and examine how artists from East and West saw the Walled City of Berlin and followed the “turning point” of 1989/90.

In the 1970s, Rainer Fetting depicted the wall as a defining element of the Kreuzberg cityscape. In his early expressive paintings, Fetting concentrated on the surface and perspective effects of the building. The walls in Wolfgang Peuker’s provocative self-portrait from 1985 form an unusual background. The artist positioned himself in front of a cityscape from birds-eye view, which unadorned depicts the reality of the division.

Roland Nicolaus was inspired by the view from his studio on Pariser Platz. Such views inspired the subjects for his artistic work. Barriers, rabbits and relics of the past shape the east-west panorama. In contrast, Wolfgang Mattheuer, from Leipzig, created pictorial compositions in the 1980s that picked up moods and expressed longings. “Und die Flügel ziehen himmelwärts” depicts prisoners trying to escape the position they’re in. However, they face an abyss; a seemingly insurmountable obstacle. This urge to break out symbolises the situation of many people in the GDR. Pressure is also an issue in Hubertus Giebes’ painting from 1990. Despite the immobile figures in the foreground, a wall has been broken open with a powerful push. Invisible forces change what seems to be firmly established. Werner Liebmann created a painting in the same year, titled “Ascension”. In an ironic allusion to the tempting promises of the future, it shows a figure floating high above the Brandenburg Gate. How the departure will end remains open.

Manfred Butzmann and Konrad Knebel, two East Berlin artists, became chroniclers of the Berlin cityscape through years of studies. They carefully exposed the historical layers and the significance this had on the present. In the exhibition, works by Gerhard Alternbourg, Wolfgang Leber, Giuseppe Madonia, Helmut Metzner, Harald Metzkes, Wolfgang Petrick and Stefan Plenkers from the Berliner Volksbank’s art collection as well as selected public and private loans will also be shown.

Exhibition film „Die Berliner Mauer und ihr Fall”

28 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH.

Hans Laabs (1915 – 2004) was one of the defining artists of the Berlin post-war period. Within the bohemian Charlottenburg art circle, he was ahead of his time within the reconstruction of the West Berlin cultural scene. In the mid-1950s, the non-conformist moved to Ibiza. Over a period of thirty years, he would spend several months a year painting. In the eighties, he returned to his studio in Luwigkirchstrasse, Berlin. During the summ

ers, he explored Salt and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Baltic coast. There he found inspiration for his late poetic works.

Works by Hans Laabs and his companions such as Alexander Camaro, Werner Heldt, Jeanne Mammen, Ludwig Gabirel Schreiber, Heinz Trökes and Hans Uhlmann from the art collection of the Berliner Volksbank, as well as loans are exhibited.

23 minutes ⓒ Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH.

At the end of January 2019, Harald Metzkes, who lives in Altlandsberg near Berlin in Brandenburg, turned 90. To mark the occasion, the Stiftung Kunstforum paid tribute to him with this exhibition.

Born in Bautzen, the artist moved to East Berlin in the mid-1950s, where he refused to comply with the official guidelines of the GDR’s cultural policy. He was soon counted among the non-conformist “Berlin School”. He is considered one of the most important artists of the GDR and of contemporary art. Harald Metzkes created multi-layered and enigmatic symbols of social realities. In doing so, he developed a style influenced in particular by 19th-century French paintings.

The art collection of the Berliner Volksbank owns almost 70 works by Harald Metzkes. In the first exhibition in the new Kunstforum, all of Harald Metzkes’ paintings from the Berliner Volksbank art collection were shown for the first time. The collection unites a stock of representative works that has grown over three decades and highlights Metzke’s development.

24 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH.

The exhibition “bankART – Drei Jahrzehnte Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank” featured high-calibre paintings, works on paper and sculptures in the Kunstforum at Budapester Straße 35.

A highlight of the exhibition was the presentation of the complete collection of works on paper by the Thuringian “picture poet” Gerhard Altenbourg, shown for the first time in this form. Sculptures by Horst Antes, René Graetz and Rolf Szymanski also offered a multifaceted insight into the field of figurative sculpture. In addition, works from the estate of the Berlin painter Bertold Haag were presented for the first time, which the Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank has been looking after since 2008.

A total of more than 80 works of art by 47 artists were shown, including works by Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Bernhard Heisig, Rainer Fetting, Horst Antes, Harald Metzkes, but also newly acquired works by Carsten Kaufhold and Britta von Willert, among others.

The selected artworks provided a representative view of the then-current state of the collection, which is one of the most prestigious corporate collections of German-German art after 1950. Curator Dr Janina Dahlmanns presented the exhibition in the rotunda of the Kunstforum under the aspect “Innenwelten – Außenwelten.”

A shock for experts, a voyage of discovery for art lovers and history buffs: Larger-than-life sculptures in Hellenistic style, statues and monumental temple reliefs of African rulers in Pharaonic regalia, colossal animal sculptures of sacred rams and lions, relief stelae with images of gods and kings, and inscriptions in hieroglyphics that are not Egyptian. The exhibition “Königsstadt Naga” showed around 130 objects that have only been excavated in the desert of Northern Sudan in the last 15 years by a team of researchers from the Egyptian Museum Berlin.

Naga was a royal city of the Meroë Empire, which was the politically and economically powerful southern neighbour of Ptolemaic-Roman Egypt from 300 BC to 350 AD. The works on loan from Sudan for this exhibition were all created in Naga in the 1st century AD. Despite this narrow limitation in space and time, they represent a spectrum of artistic diversity in sculpture, relief and architecture, ranging from African tribal art to Egyptian-inspired works to works that draw from Hellenistic-Roman sources.

As a world premiere, these artworks are an irritating broadening of the horizons of the established image of ancient art and culture. They form a bridge between Africa and the world of the Mediterranean and thus symbolically stand for a region that also today and in the future has the potential to connect continents and cultural areas. All objects were made available on loan by the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums of Sudan. The exhibition was created in cooperation with the National Museums in Berlin, funded by the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung and supported by the Verein zur Förderung des Ägyptischen Museums Berlin e.V.

Posters are a popular item used in everyday life. Their triumphant advance in the urban landscape began around 150 years ago. As this advertising medium became more and more widespread, not only graphic artists designed posters, but increasingly also artists who appropriated the medium. This mass media advertising and art form took a dynamic development in the 19th century until today. Posters are not only a medium of communication but also a mirror of society, its structures and everyday history. They often document basic political-social views, leisure, consumer and cultural behaviours in the broadest sense as well as educational and taste standards.

“KUNST FUR DIE STRASSE” gives a comprehensive overview of poster art from the Kupferstich-Kabinett of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. On display are works by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix, Oskar Kokoschka, Marc Chagall, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Manfred Butzmann and A. R. Penck.

Die Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank zeigte vom 8.9.2010 bis 19.12.2010 in Kooperation mit dem Rumänischen Kulturinstitut “Titu Maiorescu” Hinterglasikonen der Region Siebenbürgen (Transsilvanien) aus der Sammlung Hartmut van Riesen, München und der Sammlung Irina Muntean, Berlin.Weitere Leihgaben kamen aus dem Muzeul National al Unirii, Alba Iulia (Rumänien). Die rund 170 Bilder, die zum ersten Mal in einer Ausstellung zu sehen waren, gaben einen faszinierenden Einblick in die Vielfalt der rumänischen Hinterglasikonen aus dem 19. Jahrhundert.

Sammlung van Riesen, München

Die umfangreiche Sammlung historischer Hinterglasbilder des Münchner Künstlers Hartmut van Riesen und seiner Ehefrau Gisela verdankt ihre Entstehung der Begeisterung für die Hinterglasmaltechnik aus Siebenbürgen. Auslöser der Sammelfreude war eine Hinterglasikone des Heiligen Nikolaus, die das Ehepaar 1966 zum Dank als Geschenk erhielt. Das Interesse für diese volksnahe Kunstform führte die van Riesens über gezielte Ausstellungsbesuche und Kontakte zu anderen Sammlern.

Sammlung Irina Muntean, Berlin

Irina Munteans Sammlung rumänischer Hinterglasikonen aus Siebenbürgen befindet sich bereits in dritter Generation in Familienbesitz. Von klein auf mit ihnen aufgewachsen vertiefte sie ihr Wissen über die Bilder auch durch Tätigkeiten im Brukenthal-Museum in Sibiu und im Antiquitätenhandel. Die einst an den Wänden des Bauernhauses der Großmutter in Rosia (Nordsiebenbürgen) bewunderten alten Bilder, die Faszination der Farben, die märchenhaften Figuren und der mystische Zauber bei flackerndem Kerzenlicht, weckten ihre Leidenschaft und wurden zur Lebensaufgabe.

Sammlung Muzeul National al Unirii in Alba Iulia, Rumänien

In dem 1888 auf Initiative der Gesellschaft für Geschichte, Archäologie und Naturwissenschaften des Kreises Alba gegründeten Muzeul National al Unirii in Alba Iulia wurden rund 200.000 museale Objekte und Kunstwerke von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart gesammelt. Die Hinterglasikonen bilden innerhalb der religiösen Sammlungsbestände die größte Werkgruppe und stammen aus allen wichtigen Zentren dieser Kunst.

Weitere Informationen:

Zentren der Hinterglasikonen-Malerei (PDF) >>

Rumänisches Titu Maiorescu Kulturinstitut Berlin (PDF) >>

Mit freundlicher Unterstützung: