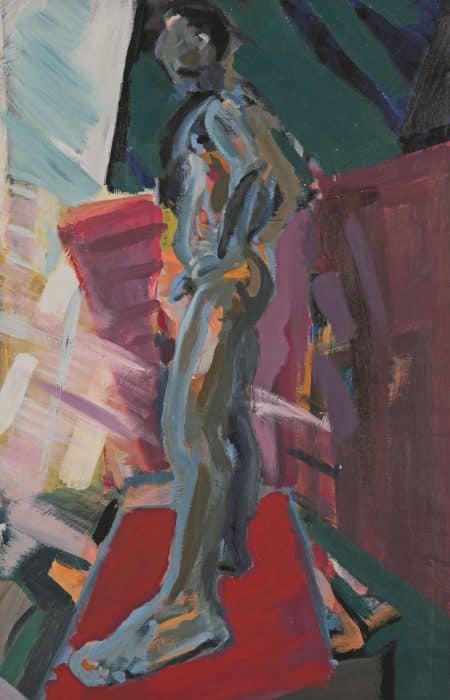

(CLASS IN WEIßENSEE! Wolfgang Peuker and His Students)

‘School begins in the classroom. The atmosphere in a classroom is determined, among other things, by the intellectual density of what is on offer, the artistic example set by the teacher and their credibility. As an image maker, I am responsible for teaching painting and hand drawing. This conscious professional distinction is important to me because it saves detours and protects against excessive demands.’[1] (translated by the author)

The exhibition KLASSE IN WEIßENSEE! Wolfgang Peuker und seine Schüler:innen (CLASS IN WEIßENSEE! Wolfgang Peuker and His Students) will open on February 11 till 5th of July 2026, at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank. It will be divided into three sections and will show Wolfgang Peuker’s works from 1989 to 2001, his work as a teacher at the Weissensee University of the Arts in Berlin and works by his students. Peuker’s paintings, in dialogue with works influenced by his teaching, create a tension between artistic production in Berlin between 1989 and the present.

[1] From: Wolfgang Peuker – Schülerinnen & Schüler: Erik Kraft, Anna Mannewitz, Sibylle Prange, Philipp Schack [About the exhibition Wolfgang Peuker – Schülerinnen und Schüler, Malerei und Grafik]. Berlin, 1995.

The effort to establish “socialist internationalism” as a cornerstone of the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) foreign policy gave rise to a wide range of transcultural contacts, exchanges and encounters. This commitment found particularly vivid expression in the GDR’s relationship with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, the so-called “brother nation”, whose struggle for liberation during the Vietnam War prompted widespread declarations of solidarity and inspired a variety of artistic productions. At the same time, the presence and creative practices of Vietnamese art students and contract workers left a lasting mark on the GDR’s cultural sphere. A closer examination of these relationships, however, reveals complex networks shaped by power structures, reciprocal empowerment, cultural ascriptions, and the interplay between freedom and constraint.

The exhibition explores the artistic and cultural exchange between the GDR and Vietnam from the 1950s through to the end of the GDR in 1990, as well as its reverberations in contemporary art. At its heart lies the question of how socialist solidarity, ideological projections and personal encounters were reflected in art, design and everyday culture—and how Vietnamese and German artists translated these experiences into aesthetic, emotional and biographical forms. The exhibition opens on 9 September as part of Berlin Art Week and will be on view until 6 December 2026 at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank.

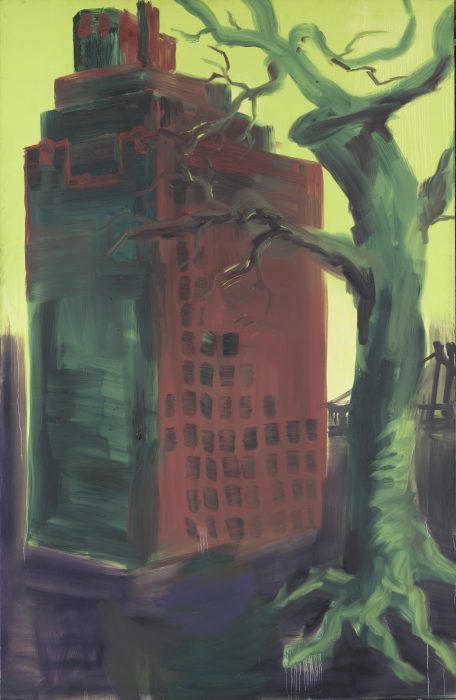

As part of Berlin Art Week 2025, the exhibition Paradies (Paradise) will open at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank on September 10. In it, contemporary artist and curator Christian Thoelke explores urban scenes from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank. He sees them as an expression and testimony of subjective world views within a culturally and politically divided Germany. Thoelke juxtaposes these works with his own works of deserted architecture from the GDR. Based on his personal experiences, the East Berlin artist reflects on the profound change in his living environment after reunification. He traces the loss of significance of these spaces as well as the conflicts and potentials of social upheaval.

The exhibition offers a multi-layered view of the urban landscape as a mirror of individual and collective transformation and builds a bridge to the present day: what processes of change is our society undergoing today and how do we experience them – as silent observers or active co-creators?

Paradies runs until December 7 and rounds off the 40th anniversary of the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank and the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank.

MENSCH BERLIN Anniversary exhibition – Celebrate 40 years of art with Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank!

The Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank are celebrating their 40th anniversary. Founded in 1985 in Berlin (West), the collection took on a special position in the West German cultural scene due to its initial focus on art from the GDR.

Under the leitmotif „Bilder vom Menschen – Bilder für Menschen“ (“Images of People – Images for People”), later expanded to include Berlin cityscapes, the founders built up one of the most important collections of figurative art of the post-war period.

With reunification, the ratio of East and West German art began to equalise. Today, the collection consists of over 1,500 works by around 200 artists. The extraordinary profile of the collection offers the opportunity to compare artistic creation in Berlin and neighbouring regions before and after the fall of the Wall.

The anniversary exhibition MENSCH BERLIN traces this development and builds a bridge from the past to the present. It shows the transformation of the art scene in Berlin and neighboring regions and a wide range of artistic perspectives perspectives – from the Berliner Schule and the Leipziger Schule to the Neue Wilde to the alternative art scene in East Berlin. During its run in Berlin, from 20 February to 22 June 2025, the exhibition will change again and again. By regularly changing the works, you will not only experience the highlights of the collection at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank, but also rarely shown works. Gain new insights with every visit and look forward to exciting new discoveries and rediscoveries.

MENSCH BERLIN in Vienna

The continuation of the exhibition at the renowned Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien is another highlight of the anniversary year. From 9 July to 31 August 2025, MENSCH BERLIN will be on display in the Austrian capital, taking the cultural heritage of this unique collection beyond the borders of Germany.

The exhibition includes works by:

Horst Antes, Elvira Bach, Annemirl Bauer, Rolf Biebl, Norbert Bisky, Christa Böhme, Karol Broniatowski, Gudrun Brüne, Manfred Butzmann, Luciano Castelli, Fritz Cremer, Christa Dichgans, E.R.N.A., Rainer Fetting, Wieland Förster, FRANEK, Ellen Fuhr, Klaus Fußmann, Hubertus Giebe, Sighard Gille, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Clemens Gröszer, Waldemar Grzimek, Bertold Haag, Angela Hampel, Bernhard Heisig, Heinz Heisig, Burkhard Held, Werner Heldt, Sabine Herrmann, Barbara Keidel, Klaus Killisch, Carl-Heinz Kliemann, Gregor-Torsten Kozik, Hans Laabs, Roland Ladwig, Helge Leiberg, Via Lewandowsky, Werner Liebmann, Rolf Lindemann, Markus Lüpertz, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Harald Metzkes, Helmut Middendorf, Roland Nicolaus, Dietrich Noßky, Barbara Quandt, Erich Fritz Reuter, Hans Scheuerecker, Cornelia Schleime, Ludwig Gabriel Schrieber, Willi Sitte, Gerd Sonntag, Hans Stein, Werner Stötzer, Strawalde, Ursula Strozynski, Rolf Szymanski, Christian Thoelke, Werner Tübke, Hans Uhlmann, Hans Vent, Ulla Walter, Trak Wendisch, Jürgen Wenzel, Bernd Zimmer and many more!

00:22:44 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH.

Conversation with FRANEK, Hubertus Giebe, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Burkhard Held, Barbara Quandt and Ulla Walter.

A film on the anniversary exhibition MENSCH BERLIN of the Stiftung KUNTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH with interviews with various artists (with English subtitles).

Production: art/beats, 2025

Duration: 00:22:44 minutes

Inter/Penetration: The Uncanniness of Seeing

The two-part exhibition, Durchdringen: Das U/unheimliche s/Sehen, by artist and curator Michael Müller is on display from 11 September 2024 to 8 December 2024 at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank as part of Berlin Art Week 2024. With a semantically and typographically layered German title, which roughly translates to “Inter/Penetration: The Uncanniness of Seeing”, it explores complementary pairs, as found, for example, in the various definitions of penetration (durchdringen), which can mean not only comprehend but also probe or scrutinise, among other things. Against this background, the exhibition also considers the relationship between the familiar (heimlich) and the mysterious (unheimlich), which psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud discussed in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny” (“Das Unheimliche”). Seemingly antithetical things, events and processes can, in fact, be mutually interrelated and inextricably connected.

In the first part of the exhibition, in which Michael Müller presents works from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank, its exhibition design and staging hinder habitual ways of seeing, compelling visitors to change their perspective and position in the darkened, compact spaces as they are denied their customary practice of moving closer to artworks. The individual works’ self-evident and familiar aspects recur in altered form, demanding they be examined with new eyes. What the viewer sees is unfamiliar and remains vague, thus revealing each artwork’s underlying layers and empty spaces, its lacunae, which previously had been concealed by supposed familiarity and assumed understanding.

In the second part of the exhibition, Michael Müller increasingly adopts the role of the artist, responding to the collection via his artworks, scrutinising it by aesthetic means. Müller makes it impossible to pigeonhole artists and works according to conventional aesthetic, stylistic, historical and substantive categories. Instead, he creates a series of independent narratives in which two works are juxtaposed and brought into dialogue.

This part of the exhibition focuses primarily on Freud’s description of the uncanny (unheimlich) furnished in his homonymous study. According to him, the uncanny stems not from the unknown and the strange but rather from the familiar, which has been repressed and rendered invisible. Freud illustrates this through its opposite, the familiar, or heimlich, a word that in German has two ambivalent levels of meaning (cosy and hidden or concealed). It is uncanny when something emerges that should have actually remained hidden and secret. Applied to art, a work is uncanny when levels surface that are generally concealed and obscured by its usual presentation and categorisation according to art-historical criteria, but suddenly come to the fore through its juxtaposition with other artworks or unexpected narrative possibilities.

Müller’s concept detaches the artworks from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank from their previous exhibition context and recontextualises them. Sculptures, paintings and works on paper appear in a new light, imbued with literary anecdotes and surrounded by unfamiliar colours and forms. The works become part of a new timeless narrative that emerges amidst Müller’s own works and loans.

For the visitors, penetrating the exhibition means engaging with new perspectives, questioning realities and discovering hidden meanings. Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank thus becomes a place of artistic intensification, where the known and the unknown meet in a fascinating way.

The exhibition includes works by:

Gerhard Altenbourg, Armando, Roger Ballen, Hans Bellmer, Asger Carlsen, Rolf Faber, Galli, René Graetz, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Bertold Haag, Martin Heinig, Hirschvogel, Ingeborg Hunzinger, Leiko Ikemura, Aneta Kajzer, Max Kaminski, Henri Michaux, Michael Müller, Michael Oppitz, Cornelia Schleime, Stefan Schröter, Werner Tübke, Max Uhlig.

Partner of:

“As you dream, so should you paint.”

(Werner Heldt)

Dreams, wistfulness, the hometown Berlin, and freedom are among the themes explored in the exhibition opening on 16 February 2024 at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank. To mark the 70th anniversary of the death of Werner Heldt (1904 – 1954) – a German painter, printmaker and poet who was one the postwar period’s most influential artists – his works are shown in dialogue with earlier and current works by Burkhard Held (* 1953). Both artists are represented in the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank, and together, they have painted a century of history. The paintings, works on paper, and prints stem from various phases in both artists’ oeuvres, with atmospheric images emerging that enter into a dialogue in the midst of historical contexts.

Werner Heldt was born in 1904 in Berlin and studied at the School of Applied Arts from 1922 to 1924, creating his first artworks there. He then attended the Academy of Arts in Berlin-Charlottenburg. Impressions of the (nocturnal) city of Berlin became the focus of his quiet, observant approach. His life took a decisive turn in the years after 1929. During the National Socialist period, Heldt fled into exile to the island of Mallorca, where he grappled with the oppressive threat arising in his homeland. In 1936, the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forced him to return to Berlin. In 1940, he entered the Second World War as a soldier, returning in 1946 from British captivity. He lived in Weissensee, in what would soon become East Berlin, until 1949, before moving to West Berlin. Heldt died in Ischia (Italy) in 1954.

Burkhard Held was born in 1953 in West Berlin. From 1972 to 1978, he studied at the University of Arts, West Berlin. From 1979 to 1980, he spent a year studying in Garrucha, Spain, on a scholarship of the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes. From 1993 until his retirement, Held was a professor at the University of Arts in Berlin. He lives and works in Berlin.

The dreamlike rendering of the inner world is a characteristic feature of Werner Heldt’s art, with the notion of dream legitimising a particular experience of reality. The dream concept reappears in a longing for freedom in faraway places, while both Werner Heldt and Burkhard Held occupy themselves with the role of time in an image.

The latter artist concentrated during the 1980s and 1990s on the subjects of figure and space in particular. For him, the two were not separate entities; space in his paintings also encompasses the figure. Spanish architecture’s distinct, austere surfaces and adjoining edges certainly influenced his figurative paintings. In later works, the figure increasingly dissolves during the painting process. In Berlin, his hometown’s cityscape evoked a longing for nature and the vastness of a landscape. During his stay in Portugal beginning in 2018, Held’s eye opened to the changing conditions of the sea. The seascape compositions in his paintings gain in colour intensity and size. High-contrast, two-dimensional elements present themselves as abstractions of the figurative.

In the Berlin am Meer series of works, which Werner Heldt created in the 1940s, the artist, as if in a daydream, transformed his destroyed hometown of Berlin into a sea. The postwar works exhibit sharply drawn lines and enlarged spaces, clearly separating these features from one another. Elements of Mallorcan architecture can be discerned.

In Werner Heldt’s Stilleben am Fenster series, created during the 1940s and 1950s, and Burkhard Held’s Berliner Fenster (1988), his native Berlin is viewed from outside and inside. That which happens outside is registered, recorded and – regarding the inner world of feelings – expressed; the window view intensifies an underlying mood of yearning.

In their stylistic forms of expression, Werner Heldt and Burkhard Held also find a similar language embodied in an objective abstract expressiveness. The spatial constellations, shapes and objects arise from the expansion of space or through the penetration, stretching and shaping of planes and the liberation from boundaries.

Differing impulses towards Berlin create a sense of tension between the moods of the two artists’ images, resulting in an intriguing dialogue substantively and stylistically.

An exhibition in collaboration with the Kunststiftung DZ BANK

13 September ‒ 10 December 2023

Opening as part of Berlin Art Week, the exhibition casts its SchlagLicht (spotlight) on a direct exchange between the genres of painting, graphic arts, sculpture, photography and video while revealing shared, thought-provoking impulses.

Works by artists in the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank ‒ a collection emphasising figurative art from the 1980s and 1990s created in Berlin and East Germany ‒ are juxtaposed with contemporary art from the DZ BANK’s collection that focuses on photographic forms of expression from 1945 to the present.

A painting by Clemens Gröszer from 1987 enters into dialogue with a photograph by artist Loredana Nemes from 2009. Whereas the calm gaze of the woman in Gröszer’s portrait seems to look away from the viewer at something in the distance, the male gaze Nemes captures in her photograph taken at a teahouse in Berlin-Neukölln disappears behind an window pane’s ornamental-patterned privacy film. The two portraits address notions of nearness and distance in equal measure. This is conveyed in the different ways they disengage from the viewer and by the political resonances they evoke, leaving the viewer to fill in the blanks.

Various art historical genres resurface in the exhibition: portraits, figural works, landscapes, architectural representations, etc. They are subjects connecting artists that go beyond generation and genre. The diversity of artistic approaches clearly illustrates that exploration of the human condition (Conditio humana) happens in each individual’s here and now, and is subject to artistic discourse as well as constant change and expansion of perspectives.

In the exhibition, a dialogue between the diverse media and materials unfolds alongside thematic emphases that include gender, society, urban spaces, and abstraction. In the true sense of the word, Rainer Fetting’s watercolours “collide” with Richard Hamilton’s painterly photographs as Rolf Lindemann’s intimate oil paintings do with Alexandra Baumgartner’s Surrealist-inspired photocollages; photographer Arno Fischer’s iconic photograph Marlene Dietrich, Moscow (1964) enters into dialogue with a bronze sculpture by René Graetz; the digitally produced “dreidimensionale Fotografien” (three-dimensional photographs), as Beate Gütschow calls her works, correspond with Wolfgang Leber’s oil painting; and Stefanie Seufert’s folded Towers, made into objects from photograms, are based on concepts of abstract and non-objective painting, as can be found in Reinhard Grimm’s canvases.

The exhibition includes works by:

Horst Antes (*1936), Alexandra Baumgartner (*1973), Manfred Butzmann (*1942), Frank Darius (*1963), Christa Dichgans (1940-2018), Rainer Fetting (*1949), Arno Fischer (1927-2011), Günther Förg (1952-2013), Nan Goldin (*1953), René Graetz (1908-1974), Reinhardt Grimm (*1958), Clemens Gröszer (1951-2014), Beate Gütschow (*1970), Richard Hamilton (1922-2011), Angela Hampel (*1956), Richard Heß (1937-2017), Sven Johne (*1976), Veronika Kellndorfer (*1962), Konrad Knebel (*1932), Hans Laabs (1915-2004), Wolfgang Leber (*1936), Via Lewandowsky (*1963), Rolf Lindemann (1933-2017), Lilly Lulay (*1985), Silke Miche (*1970), Herta Müller (*1955), Loredana Nemes (*1972), Christina Renker (*1941), Adrian Sauer (*1976), Michael Schmidt (1945-2014), Stefanie Seufert (*1969), Hans Martin Sewcz (*1955), Maria Sewcz (*1960), Andrzej Steinbach (*1983), Christian Thoelke (*1973), Wolfgang Tillmans (*1968), Ulay (1943-2020), VALIE EXPORT (*1940) und Peter Weibel (1944-2023).

Partner of:

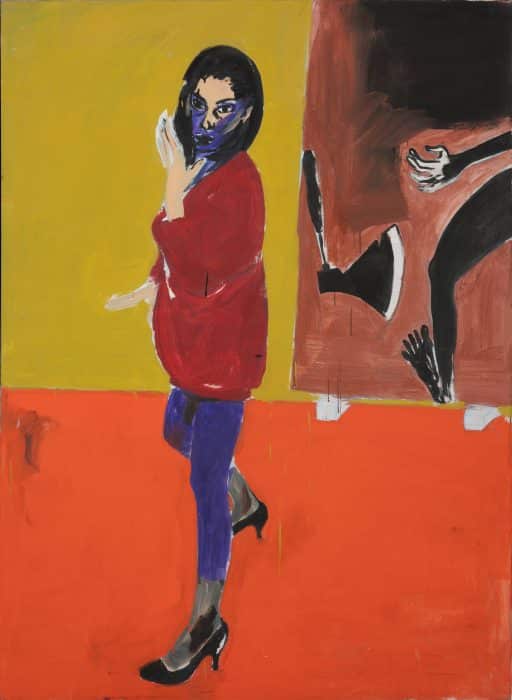

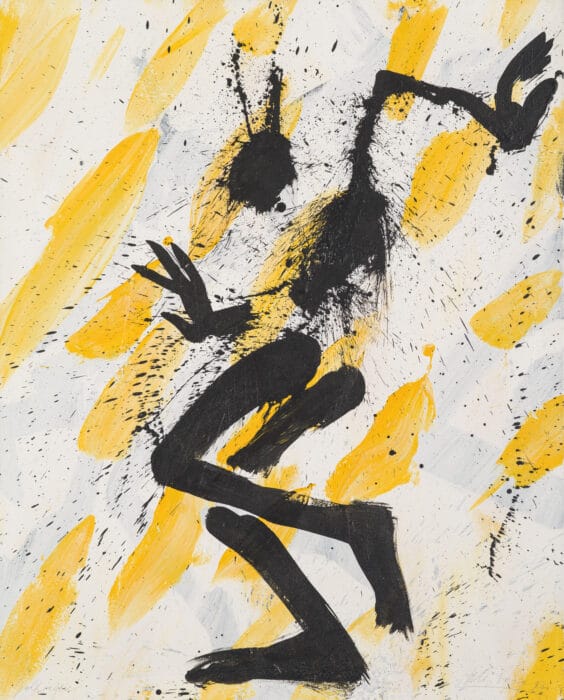

The exhibition MENSCHENBILD – der expressionistische Blick (the expressionist view) from 16th of February till 18th of June 2023 pays special attention to paintings, sculptures and works on paper that are dedicated to the theme of the figure in expressive depictions.

The focus is on works from the 1980s and 1990s, which underline the emphasis of the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank. Loans from the Kunststiftung Michels also provide selected insights into artistic positions of the early 20th century. Both, different socio-political circumstances as well as individual approaches led to diverse further developments of central ideas of Expressionism. The figurative works from different decades illustrate in the image of man the attitude to life of this time.

Featured artists includes, among others:

Elvira Bach, Georg Baselitz, Norbert Bisky, Claudia Busching, Luciano Castelli, Hartwig Ebersbach, Rainer Fetting, FRANEK, Ellen Fuhr, Sighard Gille, Otto Gleichmann, René Graetz, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Angela Hampel, Max Kaminski, Bernd Koberling, Georg Kolbe, Käthe Kollwitz, Werner Liebmann, Markus Lüpertz, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Max Pechstein, Pablo Picasso, Neo Rauch, Salomé, Rolf Sturm, Max Uhlig, Barbara Quandt and Andreas Weishaupt.

Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank

25 August ‒ 11 December 2022

Museum Nikolaikirche and Museum Ephraim-Palais

16 September ‒ 11 December 2022

From late summer 2022, the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank, together with the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, is showed the exhibition Aufbrüche. Abbrüche. Umbrüche. Kunst in Ost-Berlin 1985‒1995. Both institutions are featuring not only an exciting decade in art but two important art collections in Berlin at the same time. Using examples by 57 artists from the extensive Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the inventory of the Stadtmuseum Berlin’s (Berlin City Museum) art collections, the presentation looks back at the lively and diverse art scene in East Berlin before and after the changes brought about by the fall of the Berlin Wall. The exhibition can be viewed at three locations: at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank in Charlottenburg and at two venues of the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin in Mitte, the Museum Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas’ Church Museum) and the Museum Ephraim-Palais.

Paintings, graphics, sculptures and photographs by some 25 artists will be exhibited at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank. The current art collection (Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank), which comprised works by both West and East Berlin artists and contemporary art from the German Democratic Republic (GDR) even before the Wall came down, started in the mid-1980s. Art of the 1980s and 1990s provides a special focus in this context.

The exhibition on Kaiserdamm traces the origins of this one-of-a-kind collection of figurative art, combining exhibits from past and current acquisitions and loans from the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin. Showcasing nearly 50 works, the exhibition evocatively documents artists’ reflections on a contradictory and eventful decade, new beginnings as well as innovative approaches by women artists.

An extensive catalogue and filmed interviews accompany the exhibition project. In talks, painters Sabine Herrmann, Klaus Killisch and Sabine Peuckert, sculptor Berndt Wilde, photographer Maria Sewcz, draftswoman Uta Hünniger, and graphic artist Manfred Butzmann, recall their experiences before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Artists exhibited at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank include:

Tina Bara, Annemirl Bauer, Rolf Händler, Sylvia Hagen, Angela Hampel, Sabine Herrmann, Uta Hünniger, Ingeborg Hunzinger, Konrad Knebel, Walter Libuda, Werner Liebmann, Harald Metzkes, Helga Paris, Wolfgang Peuker, Cornelia Schleime, Baldur Schönfelder, Anna Franziska Schwarzbach, Heinrich Tessmer, Hans Ticha, Ulla Walter, Berndt Wilde.

01:05:40 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH and Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin.

Interview with Sabine Peuckert

00:00:00 till 00:08:18 Minute

Interview with Manfred Butzmann

00:08:19 till 00:19:20 Minute

Interview with Sabine Herrmann and Klaus Killisch

00:19:21 till 00:30:26 Minute

Interview with Berndt Wilde

00:30:27 till 00:42:08 Minute

Interview with Uta Hünniger

00:42:09 till 00:54:05 Minute

Interview with Maria Sewcz

00:54:06 till 01:05:40 Minute

A film to the exhibition Aufbrüche. Abbrüche. Umbrüche. Kunst in Ost-Berlin 1985 — 1995 made by Stiftung KUNTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH and the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin with interviews of various artists (with English subtitles)

Production: art/beats, 2022

Duration: 01:05:40 minutes

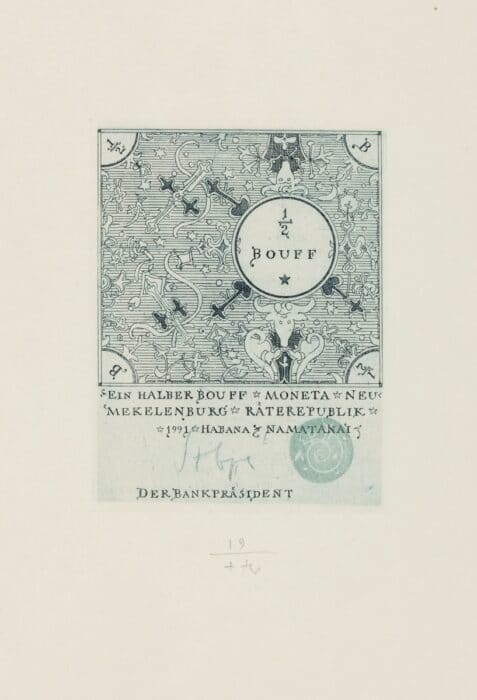

Group exhibition with works from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the Sammlung Haupt »Dreißig Silberlinge – Kunst und Geld« as well as other lenders

17 February – 19 June 2022

In this exhibition, the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank addressed the subject of money in art.

The avenues that artists explore when dealing with money in their art are creative, highly imaginative, and multifaceted. Their approaches range from artistic treatment of banknotes and coins to works of provocation. Some artists examine contradictions between material and ideal value, while others turn to conceptual assessments of social and sociopolitical aspects related to this theme.

Aesthetic means are used to question the “value” of money in our society: How important is money to each one of us? Can you escape your own economic significance? Can art ever be free? To what extent are artists themselves caught in the cogs of securing their existence and affected by increases in value and market power?

A recurring artistic focus is a critique of capitalism, but also the complex relationships between art and commerce. The symbolism of American dollar bills, which are typically associated with the USA as a monetary superpower, has been broken down and recontextualized by artists such as Anne Jud and Andy Warhol.

In the years following the political reunification of Germany, an artist’s group in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district established a new currency called “Knochengeld” (bone money). In this project, some 53 international and Berlin based artists dealt with the profound social change experienced in the early 1990s, brought about by adopting a market economy in the wake of monetary union and reunification.

Following the introduction of the euro around ten years later, artists used shredded DM (Deutsche Mark) notes as materials for the most diverse works. This treatment of now worthless banknotes provided an opportunity to reflect on the value of the material and the fragility of the monetary system.

Some artistic explorations took up the subject of “gold” ‒ for instance, in works by Helge Leiberg, Albrecht Fersch and Michael Müller. Other artists, including Horst Hussel, created imaginary art currencies.

The art market and the values of art as merchandise and speculative assets are also addressed as a central theme. Ultimately, the NFT (non-fungible token) art trend forces us to rethink the significance and uniqueness of digital objects.

The exhibition CASH on the Wall presents paintings, objects, sculptures, prints, collages, photographs, installations and videos. The exhibits are from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the Sammlung Haupt »Dreißig Silberlinge – Kunst und Geld«, as well as other lenders.

Artists whose works are on view include: Katharina Arndt, Joseph Beuys, Bewegung NURR, Victor Bonato, Dadara, Annett Deppe, WP Eberhard Eggers, Thomas Eller, Elmgreen & Dragset, Albrecht Fersch, Ueli Fuchser, Hannah Heer, Markus Huemer, Uta Hünniger, Horst Hussel, Robert Jelinek, Anne Jud, Vollrad Kutscher, Alicja Kwade, Christin Lahr, Helge Leiberg, Via Lewandowsky, Lies Maculan, Laurent Mignonneau, Lee Mingwei, Michael Müller, Roland Nicolaus, Wolfgang Nieblich, Ingrid Pitzer, Anahita Razmi, Werner Schmiedel, Michael Schoenholtz, Reiner Schwarz, Justine Smith, Christa Sommerer, Gerd Sonntag, Daniel Spoerri, Klaus Staeck, Hans Ticha, Timm Ulrichs, Philipp Valenta, Petrus Wandrey, Andy Warhol, Caroline Weihrauch, Vadim Zakharov.