MENSCH BERLIN Anniversary exhibition – Celebrate 40 years of art with Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank!

The Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank are celebrating their 40th anniversary. Founded in 1985 in Berlin (West), the collection took on a special position in the West German cultural scene due to its initial focus on art from the GDR.

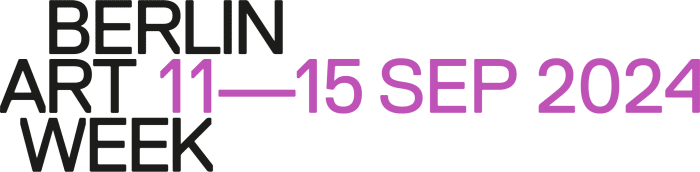

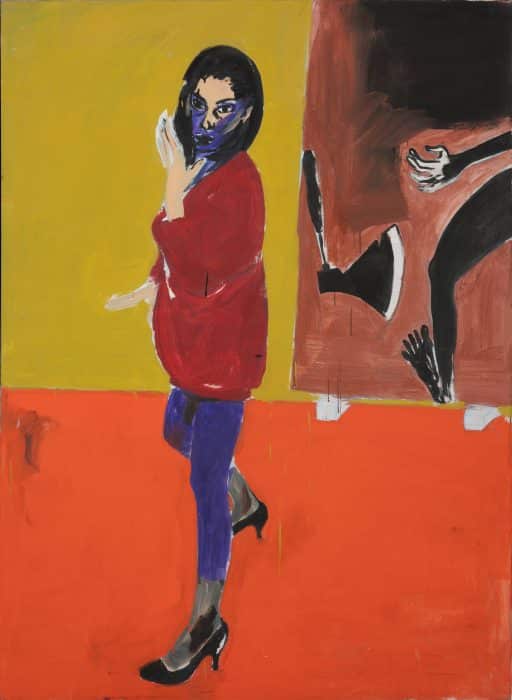

Under the leitmotif „Bilder vom Menschen – Bilder für Menschen“ (“Images of People – Images for People”), later expanded to include Berlin cityscapes, the founders built up one of the most important collections of figurative art of the post-war period.

With reunification, the ratio of East and West German art began to equalise. Today, the collection consists of over 1,500 works by around 200 artists. The extraordinary profile of the collection offers the opportunity to compare artistic creation in Berlin and neighbouring regions before and after the fall of the Wall.

The anniversary exhibition MENSCH BERLIN traces this development and builds a bridge from the past to the present. It shows the transformation of the art scene in Berlin and neighboring regions and a wide range of artistic perspectives perspectives – from the Berliner Schule and the Leipziger Schule to the Neue Wilde to the alternative art scene in East Berlin. During its run in Berlin, from 20 February to 22 June 2025, the exhibition will change again and again. By regularly changing the works, you will not only experience the highlights of the collection at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank, but also rarely shown works. Gain new insights with every visit and look forward to exciting new discoveries and rediscoveries.

MENSCH BERLIN in Vienna

The continuation of the exhibition at the renowned Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien is another highlight of the anniversary year. From 9 July to 31 August 2025, MENSCH BERLIN will be on display in the Austrian capital, taking the cultural heritage of this unique collection beyond the borders of Germany.

The exhibition includes works by:

Horst Antes, Elvira Bach, Annemirl Bauer, Rolf Biebl, Norbert Bisky, Christa Böhme, Karol Broniatowski, Gudrun Brüne, Manfred Butzmann, Luciano Castelli, Fritz Cremer, Christa Dichgans, E.R.N.A., Rainer Fetting, Wieland Förster, FRANEK, Ellen Fuhr, Klaus Fußmann, Hubertus Giebe, Sighard Gille, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Clemens Gröszer, Waldemar Grzimek, Bertold Haag, Angela Hampel, Bernhard Heisig, Heinz Heisig, Burkhard Held, Werner Heldt, Sabine Herrmann, Barbara Keidel, Klaus Killisch, Carl-Heinz Kliemann, Gregor-Torsten Kozik, Hans Laabs, Roland Ladwig, Helge Leiberg, Via Lewandowsky, Werner Liebmann, Rolf Lindemann, Markus Lüpertz, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Harald Metzkes, Helmut Middendorf, Roland Nicolaus, Dietrich Noßky, Barbara Quandt, Erich Fritz Reuter, Hans Scheuerecker, Cornelia Schleime, Ludwig Gabriel Schrieber, Willi Sitte, Gerd Sonntag, Hans Stein, Werner Stötzer, Strawalde, Ursula Strozynski, Rolf Szymanski, Christian Thoelke, Werner Tübke, Hans Uhlmann, Hans Vent, Ulla Walter, Trak Wendisch, Jürgen Wenzel, Bernd Zimmer and many more!

00:22:44 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH.

Conversation with FRANEK, Hubertus Giebe, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Burkhard Held, Barbara Quandt and Ulla Walter.

A film on the anniversary exhibition MENSCH BERLIN of the Stiftung KUNTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH with interviews with various artists (with English subtitles).

Production: art/beats, 2025

Duration: 00:22:44 minutes

00:00:27 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH.

Production: art/beats, 2025

Duration: 00:00:27 minutes

A new exhibition will open at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank on 10 September to coincide with Berlin Art Week 2025. The focus is on the Dresden-born, Berlin-based artist Via Lewandowsky, who will curate the exhibition and also contribute his own works. With his eventful past as a subversive GDR artist who travelled to the West shortly before reunification, Lewandowsky’s work fits perfectly into the context of Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank. In combination with works from this important collection of art from East and West, exciting perspectives on the contemporary artistic processing of German-German history and the period after reunification are created. The exhibition runs until 7 December and rounds off the 40th anniversary of the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank and the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank.

Transformationsprozesse in der zeitgenössischen bildenden Kunst in Deutschland.

Ein Projekt von Gabriele Muschter und Uwe Warnke, 2014-2021. Wird von Uwe Warnke aktuell fortgeführt.

00:25:06 Minuten © Uwe Warnke für den Film; Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH für die Website.

Interview mit Ruth Wolf Rehfeldt (1932–2024) am 13. Juni 2019 in Berlin, geführt von Gabriele Muschter und Uwe Warnke.

Produktion: Uwe Warnke und Olaf Voigtländer, 2025

Dauer: 00:25:44 Minuten

Zeithistorische Interviews mit bildenden Künstler:innen, Kunstakteuren, Museumsdirektoren und vielen mehr aus der DDR und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Gabriele Muschter (1943-2023), lebte in Berlin und Liedekahle (Brandenburg), Kunstwissenschaftlerin, Galeristin, arbeitete auch als Kuratorin von internationalen Kunstausstellungen, Autorin, Redakteurin. Zahlreiche Veröffentlichungen, vor allem zur ostdeutschen Kunst und Fotografie.

Uwe Warnke (1956), lebt in Berlin, Autor, Verleger, Kurator. 1982 Gründer der ersten illegal erschienenen Künstlerzeitschrift in der DDR, Entwerter/Oder. 1990 Gründung des Uwe Warnke Verlages, Ausstellungen zur Visuellen Poesie, zur Poesie des Untergrunds, zur Buchkunst und zur zeitgenössischen Fotografie. Texte zur Literatur, Fotografie, Buchkunst und Jazz.

Inter/Penetration: The Uncanniness of Seeing

The two-part exhibition, Durchdringen: Das U/unheimliche s/Sehen, by artist and curator Michael Müller is on display from 11 September 2024 to 8 December 2024 at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank as part of Berlin Art Week 2024. With a semantically and typographically layered German title, which roughly translates to “Inter/Penetration: The Uncanniness of Seeing”, it explores complementary pairs, as found, for example, in the various definitions of penetration (durchdringen), which can mean not only comprehend but also probe or scrutinise, among other things. Against this background, the exhibition also considers the relationship between the familiar (heimlich) and the mysterious (unheimlich), which psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud discussed in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny” (“Das Unheimliche”). Seemingly antithetical things, events and processes can, in fact, be mutually interrelated and inextricably connected.

In the first part of the exhibition, in which Michael Müller presents works from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank, its exhibition design and staging hinder habitual ways of seeing, compelling visitors to change their perspective and position in the darkened, compact spaces as they are denied their customary practice of moving closer to artworks. The individual works’ self-evident and familiar aspects recur in altered form, demanding they be examined with new eyes. What the viewer sees is unfamiliar and remains vague, thus revealing each artwork’s underlying layers and empty spaces, its lacunae, which previously had been concealed by supposed familiarity and assumed understanding.

In the second part of the exhibition, Michael Müller increasingly adopts the role of the artist, responding to the collection via his artworks, scrutinising it by aesthetic means. Müller makes it impossible to pigeonhole artists and works according to conventional aesthetic, stylistic, historical and substantive categories. Instead, he creates a series of independent narratives in which two works are juxtaposed and brought into dialogue.

This part of the exhibition focuses primarily on Freud’s description of the uncanny (unheimlich) furnished in his homonymous study. According to him, the uncanny stems not from the unknown and the strange but rather from the familiar, which has been repressed and rendered invisible. Freud illustrates this through its opposite, the familiar, or heimlich, a word that in German has two ambivalent levels of meaning (cosy and hidden or concealed). It is uncanny when something emerges that should have actually remained hidden and secret. Applied to art, a work is uncanny when levels surface that are generally concealed and obscured by its usual presentation and categorisation according to art-historical criteria, but suddenly come to the fore through its juxtaposition with other artworks or unexpected narrative possibilities.

Müller’s concept detaches the artworks from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank from their previous exhibition context and recontextualises them. Sculptures, paintings and works on paper appear in a new light, imbued with literary anecdotes and surrounded by unfamiliar colours and forms. The works become part of a new timeless narrative that emerges amidst Müller’s own works and loans.

For the visitors, penetrating the exhibition means engaging with new perspectives, questioning realities and discovering hidden meanings. Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank thus becomes a place of artistic intensification, where the known and the unknown meet in a fascinating way.

The exhibition includes works by:

Gerhard Altenbourg, Armando, Roger Ballen, Hans Bellmer, Asger Carlsen, Rolf Faber, Galli, René Graetz, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Bertold Haag, Martin Heinig, Hirschvogel, Ingeborg Hunzinger, Leiko Ikemura, Aneta Kajzer, Max Kaminski, Henri Michaux, Michael Müller, Michael Oppitz, Cornelia Schleime, Stefan Schröter, Werner Tübke, Max Uhlig.

Partner of:

“As you dream, so should you paint.”

(Werner Heldt)

Dreams, wistfulness, the hometown Berlin, and freedom are among the themes explored in the exhibition opening on 16 February 2024 at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank. To mark the 70th anniversary of the death of Werner Heldt (1904 – 1954) – a German painter, printmaker and poet who was one the postwar period’s most influential artists – his works are shown in dialogue with earlier and current works by Burkhard Held (* 1953). Both artists are represented in the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank, and together, they have painted a century of history. The paintings, works on paper, and prints stem from various phases in both artists’ oeuvres, with atmospheric images emerging that enter into a dialogue in the midst of historical contexts.

Werner Heldt was born in 1904 in Berlin and studied at the School of Applied Arts from 1922 to 1924, creating his first artworks there. He then attended the Academy of Arts in Berlin-Charlottenburg. Impressions of the (nocturnal) city of Berlin became the focus of his quiet, observant approach. His life took a decisive turn in the years after 1929. During the National Socialist period, Heldt fled into exile to the island of Mallorca, where he grappled with the oppressive threat arising in his homeland. In 1936, the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forced him to return to Berlin. In 1940, he entered the Second World War as a soldier, returning in 1946 from British captivity. He lived in Weissensee, in what would soon become East Berlin, until 1949, before moving to West Berlin. Heldt died in Ischia (Italy) in 1954.

Burkhard Held was born in 1953 in West Berlin. From 1972 to 1978, he studied at the University of Arts, West Berlin. From 1979 to 1980, he spent a year studying in Garrucha, Spain, on a scholarship of the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes. From 1993 until his retirement, Held was a professor at the University of Arts in Berlin. He lives and works in Berlin.

The dreamlike rendering of the inner world is a characteristic feature of Werner Heldt’s art, with the notion of dream legitimising a particular experience of reality. The dream concept reappears in a longing for freedom in faraway places, while both Werner Heldt and Burkhard Held occupy themselves with the role of time in an image.

The latter artist concentrated during the 1980s and 1990s on the subjects of figure and space in particular. For him, the two were not separate entities; space in his paintings also encompasses the figure. Spanish architecture’s distinct, austere surfaces and adjoining edges certainly influenced his figurative paintings. In later works, the figure increasingly dissolves during the painting process. In Berlin, his hometown’s cityscape evoked a longing for nature and the vastness of a landscape. During his stay in Portugal beginning in 2018, Held’s eye opened to the changing conditions of the sea. The seascape compositions in his paintings gain in colour intensity and size. High-contrast, two-dimensional elements present themselves as abstractions of the figurative.

In the Berlin am Meer series of works, which Werner Heldt created in the 1940s, the artist, as if in a daydream, transformed his destroyed hometown of Berlin into a sea. The postwar works exhibit sharply drawn lines and enlarged spaces, clearly separating these features from one another. Elements of Mallorcan architecture can be discerned.

In Werner Heldt’s Stilleben am Fenster series, created during the 1940s and 1950s, and Burkhard Held’s Berliner Fenster (1988), his native Berlin is viewed from outside and inside. That which happens outside is registered, recorded and – regarding the inner world of feelings – expressed; the window view intensifies an underlying mood of yearning.

In their stylistic forms of expression, Werner Heldt and Burkhard Held also find a similar language embodied in an objective abstract expressiveness. The spatial constellations, shapes and objects arise from the expansion of space or through the penetration, stretching and shaping of planes and the liberation from boundaries.

Differing impulses towards Berlin create a sense of tension between the moods of the two artists’ images, resulting in an intriguing dialogue substantively and stylistically.

An exhibition in collaboration with the Kunststiftung DZ BANK

13 September ‒ 10 December 2023

Opening as part of Berlin Art Week, the exhibition casts its SchlagLicht (spotlight) on a direct exchange between the genres of painting, graphic arts, sculpture, photography and video while revealing shared, thought-provoking impulses.

Works by artists in the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank ‒ a collection emphasising figurative art from the 1980s and 1990s created in Berlin and East Germany ‒ are juxtaposed with contemporary art from the DZ BANK’s collection that focuses on photographic forms of expression from 1945 to the present.

A painting by Clemens Gröszer from 1987 enters into dialogue with a photograph by artist Loredana Nemes from 2009. Whereas the calm gaze of the woman in Gröszer’s portrait seems to look away from the viewer at something in the distance, the male gaze Nemes captures in her photograph taken at a teahouse in Berlin-Neukölln disappears behind an window pane’s ornamental-patterned privacy film. The two portraits address notions of nearness and distance in equal measure. This is conveyed in the different ways they disengage from the viewer and by the political resonances they evoke, leaving the viewer to fill in the blanks.

Various art historical genres resurface in the exhibition: portraits, figural works, landscapes, architectural representations, etc. They are subjects connecting artists that go beyond generation and genre. The diversity of artistic approaches clearly illustrates that exploration of the human condition (Conditio humana) happens in each individual’s here and now, and is subject to artistic discourse as well as constant change and expansion of perspectives.

In the exhibition, a dialogue between the diverse media and materials unfolds alongside thematic emphases that include gender, society, urban spaces, and abstraction. In the true sense of the word, Rainer Fetting’s watercolours “collide” with Richard Hamilton’s painterly photographs as Rolf Lindemann’s intimate oil paintings do with Alexandra Baumgartner’s Surrealist-inspired photocollages; photographer Arno Fischer’s iconic photograph Marlene Dietrich, Moscow (1964) enters into dialogue with a bronze sculpture by René Graetz; the digitally produced “dreidimensionale Fotografien” (three-dimensional photographs), as Beate Gütschow calls her works, correspond with Wolfgang Leber’s oil painting; and Stefanie Seufert’s folded Towers, made into objects from photograms, are based on concepts of abstract and non-objective painting, as can be found in Reinhard Grimm’s canvases.

The exhibition includes works by:

Horst Antes (*1936), Alexandra Baumgartner (*1973), Manfred Butzmann (*1942), Frank Darius (*1963), Christa Dichgans (1940-2018), Rainer Fetting (*1949), Arno Fischer (1927-2011), Günther Förg (1952-2013), Nan Goldin (*1953), René Graetz (1908-1974), Reinhardt Grimm (*1958), Clemens Gröszer (1951-2014), Beate Gütschow (*1970), Richard Hamilton (1922-2011), Angela Hampel (*1956), Richard Heß (1937-2017), Sven Johne (*1976), Veronika Kellndorfer (*1962), Konrad Knebel (*1932), Hans Laabs (1915-2004), Wolfgang Leber (*1936), Via Lewandowsky (*1963), Rolf Lindemann (1933-2017), Lilly Lulay (*1985), Silke Miche (*1970), Herta Müller (*1955), Loredana Nemes (*1972), Christina Renker (*1941), Adrian Sauer (*1976), Michael Schmidt (1945-2014), Stefanie Seufert (*1969), Hans Martin Sewcz (*1955), Maria Sewcz (*1960), Andrzej Steinbach (*1983), Christian Thoelke (*1973), Wolfgang Tillmans (*1968), Ulay (1943-2020), VALIE EXPORT (*1940) und Peter Weibel (1944-2023).

Partner of:

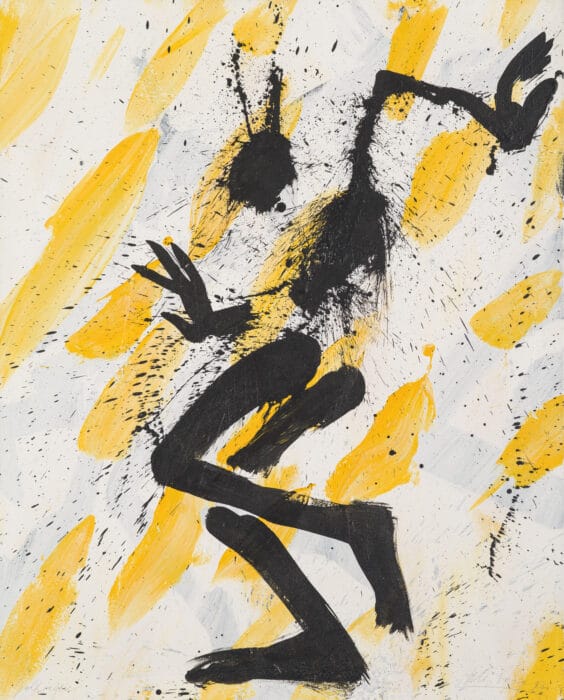

The exhibition MENSCHENBILD – der expressionistische Blick (the expressionist view) from 16th of February till 18th of June 2023 pays special attention to paintings, sculptures and works on paper that are dedicated to the theme of the figure in expressive depictions.

The focus is on works from the 1980s and 1990s, which underline the emphasis of the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank. Loans from the Kunststiftung Michels also provide selected insights into artistic positions of the early 20th century. Both, different socio-political circumstances as well as individual approaches led to diverse further developments of central ideas of Expressionism. The figurative works from different decades illustrate in the image of man the attitude to life of this time.

Featured artists includes, among others:

Elvira Bach, Georg Baselitz, Norbert Bisky, Claudia Busching, Luciano Castelli, Hartwig Ebersbach, Rainer Fetting, FRANEK, Ellen Fuhr, Sighard Gille, Otto Gleichmann, René Graetz, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Angela Hampel, Max Kaminski, Bernd Koberling, Georg Kolbe, Käthe Kollwitz, Werner Liebmann, Markus Lüpertz, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Max Pechstein, Pablo Picasso, Neo Rauch, Salomé, Rolf Sturm, Max Uhlig, Barbara Quandt and Andreas Weishaupt.

Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank

25 August ‒ 11 December 2022

Museum Nikolaikirche and Museum Ephraim-Palais

16 September ‒ 11 December 2022

From late summer 2022, the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank, together with the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, is showed the exhibition Aufbrüche. Abbrüche. Umbrüche. Kunst in Ost-Berlin 1985‒1995. Both institutions are featuring not only an exciting decade in art but two important art collections in Berlin at the same time. Using examples by 57 artists from the extensive Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the inventory of the Stadtmuseum Berlin’s (Berlin City Museum) art collections, the presentation looks back at the lively and diverse art scene in East Berlin before and after the changes brought about by the fall of the Berlin Wall. The exhibition can be viewed at three locations: at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank in Charlottenburg and at two venues of the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin in Mitte, the Museum Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas’ Church Museum) and the Museum Ephraim-Palais.

Paintings, graphics, sculptures and photographs by some 25 artists will be exhibited at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank. The current art collection (Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank), which comprised works by both West and East Berlin artists and contemporary art from the German Democratic Republic (GDR) even before the Wall came down, started in the mid-1980s. Art of the 1980s and 1990s provides a special focus in this context.

The exhibition on Kaiserdamm traces the origins of this one-of-a-kind collection of figurative art, combining exhibits from past and current acquisitions and loans from the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin. Showcasing nearly 50 works, the exhibition evocatively documents artists’ reflections on a contradictory and eventful decade, new beginnings as well as innovative approaches by women artists.

An extensive catalogue and filmed interviews accompany the exhibition project. In talks, painters Sabine Herrmann, Klaus Killisch and Sabine Peuckert, sculptor Berndt Wilde, photographer Maria Sewcz, draftswoman Uta Hünniger, and graphic artist Manfred Butzmann, recall their experiences before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Artists exhibited at the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank include:

Tina Bara, Annemirl Bauer, Rolf Händler, Sylvia Hagen, Angela Hampel, Sabine Herrmann, Uta Hünniger, Ingeborg Hunzinger, Konrad Knebel, Walter Libuda, Werner Liebmann, Harald Metzkes, Helga Paris, Wolfgang Peuker, Cornelia Schleime, Baldur Schönfelder, Anna Franziska Schwarzbach, Heinrich Tessmer, Hans Ticha, Ulla Walter, Berndt Wilde.

01:05:40 minutes © Stiftung KUNSTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH and Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin.

Interview with Sabine Peuckert

00:00:00 till 00:08:18 Minute

Interview with Manfred Butzmann

00:08:19 till 00:19:20 Minute

Interview with Sabine Herrmann and Klaus Killisch

00:19:21 till 00:30:26 Minute

Interview with Berndt Wilde

00:30:27 till 00:42:08 Minute

Interview with Uta Hünniger

00:42:09 till 00:54:05 Minute

Interview with Maria Sewcz

00:54:06 till 01:05:40 Minute

A film to the exhibition Aufbrüche. Abbrüche. Umbrüche. Kunst in Ost-Berlin 1985 — 1995 made by Stiftung KUNTFORUM der Berliner Volksbank gGmbH and the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin with interviews of various artists (with English subtitles)

Production: art/beats, 2022

Duration: 01:05:40 minutes

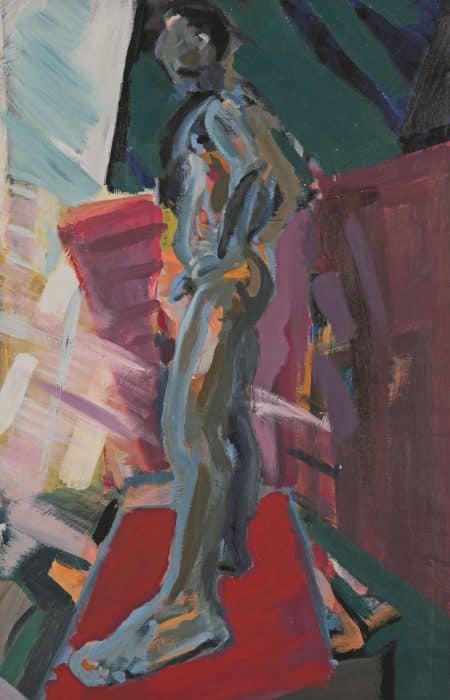

Group exhibition with works from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the Sammlung Haupt »Dreißig Silberlinge – Kunst und Geld« as well as other lenders

17 February – 19 June 2022

In this exhibition, the Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank addressed the subject of money in art.

The avenues that artists explore when dealing with money in their art are creative, highly imaginative, and multifaceted. Their approaches range from artistic treatment of banknotes and coins to works of provocation. Some artists examine contradictions between material and ideal value, while others turn to conceptual assessments of social and sociopolitical aspects related to this theme.

Aesthetic means are used to question the “value” of money in our society: How important is money to each one of us? Can you escape your own economic significance? Can art ever be free? To what extent are artists themselves caught in the cogs of securing their existence and affected by increases in value and market power?

A recurring artistic focus is a critique of capitalism, but also the complex relationships between art and commerce. The symbolism of American dollar bills, which are typically associated with the USA as a monetary superpower, has been broken down and recontextualized by artists such as Anne Jud and Andy Warhol.

In the years following the political reunification of Germany, an artist’s group in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district established a new currency called “Knochengeld” (bone money). In this project, some 53 international and Berlin based artists dealt with the profound social change experienced in the early 1990s, brought about by adopting a market economy in the wake of monetary union and reunification.

Following the introduction of the euro around ten years later, artists used shredded DM (Deutsche Mark) notes as materials for the most diverse works. This treatment of now worthless banknotes provided an opportunity to reflect on the value of the material and the fragility of the monetary system.

Some artistic explorations took up the subject of “gold” ‒ for instance, in works by Helge Leiberg, Albrecht Fersch and Michael Müller. Other artists, including Horst Hussel, created imaginary art currencies.

The art market and the values of art as merchandise and speculative assets are also addressed as a central theme. Ultimately, the NFT (non-fungible token) art trend forces us to rethink the significance and uniqueness of digital objects.

The exhibition CASH on the Wall presents paintings, objects, sculptures, prints, collages, photographs, installations and videos. The exhibits are from the Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank and the Sammlung Haupt »Dreißig Silberlinge – Kunst und Geld«, as well as other lenders.

Artists whose works are on view include: Katharina Arndt, Joseph Beuys, Bewegung NURR, Victor Bonato, Dadara, Annett Deppe, WP Eberhard Eggers, Thomas Eller, Elmgreen & Dragset, Albrecht Fersch, Ueli Fuchser, Hannah Heer, Markus Huemer, Uta Hünniger, Horst Hussel, Robert Jelinek, Anne Jud, Vollrad Kutscher, Alicja Kwade, Christin Lahr, Helge Leiberg, Via Lewandowsky, Lies Maculan, Laurent Mignonneau, Lee Mingwei, Michael Müller, Roland Nicolaus, Wolfgang Nieblich, Ingrid Pitzer, Anahita Razmi, Werner Schmiedel, Michael Schoenholtz, Reiner Schwarz, Justine Smith, Christa Sommerer, Gerd Sonntag, Daniel Spoerri, Klaus Staeck, Hans Ticha, Timm Ulrichs, Philipp Valenta, Petrus Wandrey, Andy Warhol, Caroline Weihrauch, Vadim Zakharov.

The first exhibition of 2021 at Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank is a joint project. “WIR. Nähe und Distanz – Jubiläumsausstellung mit Werken aus der Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank” is marked by four jubilees: the Kunstforum and the art collection turn 35 years old, Werkstatt für Kreative was founded 15 years ago and last but not least Berliner Volksbank celebrates its 75th anniversary. Commemorating these occasions, fourteen employees of Berliner Volksbank eG co-curated the exhibition together with the two art-historians from Stiftung KUNSTFORUM.

Balancing closeness and distance creates a new kind of community. Absence and presence, distance and attraction generate a diverse interplay.

In terms of content, the exhibition is on the one hand about the personal perspective of the guest curators. On the other hand, historical and current issues, different perspectives on the city and society come into focus. As a result, the exhibition shows the diversity of the collection.

On view are works from the art collection of Berliner Volksbank including artworks created by: Hermann Albert, Gerhard Altenbourg, Rolf Biebl, Christa Dichgans, Klaus Fußmann, Sylvia Hagen, Angela Hampel, Werner Heldt, Thomas Hornemann, Ingeborg Hunzinger, Karl-Ludwig Lange, Wolfgang Leber, Markus Lüpertz, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Harald Metzkes, Silke Miche, Kurt Mühlenhaupt, Roland Nicolaus, Wolfgang Peuker, Erich Fritz Reuter, Cornelia Schleime, Ludwig Gabriel Schreiber, Ruth Tesmar, Christian Thoelke, Hans Uhlmann and Ulla Walter.

A catalogue has been published for the exhibition and is available for purchase here: [Publications]

Catalogue text by co-curator, Dr Janina Dahlmanns

The year 2020 was marked by the pandemic – and the question of proximity and distance left its mark on people’s everyday lives, as well as on the work of the Berliner Volksbank curatorial team. Could we still provide safety with a physical distance of 1.5 metres? Was there closeness and a shared sense of “we” even in the virtual space of the video conference? Or more generally: does solidarity and community grow even / despite / because of spatial distance?

As topical as these questions were, there were also fundamental, philosophical thoughts on this subject. The parable “Die Stachelschweine” by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, created in 1851, already addresses the dilemma of closeness and distance in coexistence: a group of porcupines has the need for physical warmth – at the same time, however, the neighbour’s quills hurt the closer the individuals get to each other. It is therefore necessary to find the ideal distance in order to use the communal warmth without getting pricked by the other’s quills. This conflict can be transferred to humans. On the one hand, there is the strong human need for closeness, for solidarity and community, for friendship and love. On the other hand, people also strive for individualism and self-determination – some have a need for peace and solitude.

In this field of tension between closeness and distance, it is important to find a balance. The challenges lie in the personal sphere, in the shaping of private relationships of all kinds: from love to friendship and family, to everyday encounters with others.

Living conditions in a big city, like Berlin, tests the ability for each individual to find his or her way in the hustle and bustle of anonymous crowds. At the same time, it is precisely the crowd of different people that makes the city so fascinating and lively. Community, cohesion and pleasure are contrasted with loneliness, isolation and forlornness.

The relationship between the individual and society, to the political situation and to history, can also be considered in terms of proximity and distance. It is a question of how strongly the individual allows his or her actions to be influenced by the social environment and, at the same time, how historical developments guide personal actions and feelings.

These questions are a source of constant new debates, considerations and reflections in order to determine and define one’s own position. It is precisely with the means of art that the complexity of positive and negative emotions and needs can be depicted.

The Kunstsammlung der Berliner Volksbank focuses on figurative art, so unsurprisingly the image of the human being is strongly represented. Thus, the emotional state of man and the numerous related issues of man as well as the individual within society often become the subject of our art. The environment of the human being, the concrete, the metaphorical or the emotional space, also is repeatedly found in these works of art. Thus, it made sense to select works which included the idea of ‘proximity and distance’ and to approach it with a variety of artistic positions.

Artistic self-portraits

The main subject of the exhibition, Klaus Fußmann’s “Atelier mit roter Jacke,” sets the tone for the overall theme: Distance is created by initially missing the presence of a human being. At first glance, this distance is unsettling. However, what the depiction displays forcefully is the artist’s personality. Although he has left his studio, the objects in the room, such as paint tubes and pots, demonstrate activity. The white wall stands for the space to be filled with art. The signal red jacket echoes the creative energy of the artist.

In contrast, Christa Dichgans uses countless small figures in “Begegnung mit den Ichs” to illustrate the many facets of her identity. In the foreground, she herself is seen painting an angel figure, which can be understood as a symbol of the departure and free creativity of artistic creation.

In Wolfgang Mattheuer’s “Selbstbildnis,” the artist shows himself with a brush in his hand as a “Bild im Bild”(picture in a picture) in the form of a portrait on an easel. Through the open windows and the reflections of the cityscape, Mattheuer opens up the studio space and refers to his surroundings: he allows the world from outside to permeate into his interior and thematises the interrelation in art, mirrored and transformed many times over. The complex process of stepping back to artistically survey the truth and at the same time reproduce it in detail is indicated by the interweaving of the two spaces.

Loneliness

Mattheuer’s “Blinder Mann” leads the viewer into a group of works dealing with human loneliness. The monochrome painted figure appears petrified and sits without any connection to its environment in front of a dark background. The blindness illustrated by the closed eyes prevents contact with the surroundings.

This impossibility of connection is also shown in Ingeborg Hunzinger’s marble sculpture “Über die Schulter.” The block-like form of the figure prevents any interaction with the surrounding space; it is entirely focused on itself. She appears completely alone and left to her own devices. In her isolation, she is completely on her own. But the effect also varies: possibly the figure also protects itself from its environment, withdraws voluntarily and deliberately does not allow its surroundings to get close to it.

The figures in Wolfgang Leber’s “Auf der Galerie” also move in isolation in a convoluted space, possibly a situation in a railway station or a shopping centre. The figures do not look at each other and their paths do not cross either, an encounter does not seem possible.

Karl-Ludwig Lange’s “Fast im Warmen” further increases the isolation of the individual. The shadowy, frontal figure faces the viewer directly – but the blurring of the details and the cloudy colour scheme convey a concrete as well as metaphorical distance.

Love

The juxtaposition of the need for closeness and distance is a recurring theme in the representation of love in art. In Ruth Tesmar’s “Unter Wasser – Schweben,” the silhouettes of a woman and a man move as if weightless in a blue room. Their bodies float next to each other and fit into each other’s forms, yet they do not touch. In this poetic image, water can be understood as a metaphor for life: The couple floats through close to each other and each remains autonomous.

Hans Uhlmann’s bronze “Weibliche Gruppe” shows a touching image of physical intimacy. The formally minimalist bodies are drawn in a common outline, their arms resting on each other’s bodies, while their heads virtually merge.

Angela Hampel’s lithograph “Dich spüren will ich…” (I want to feel you), on the other hand, speaks of the longing for this physical contact, as the title suggests. The female figure illustrates the conflict of this desire. The figure with a piercing gaze puts her arm around her own shoulder as if she wants to embrace herself. In the other hand, she holds a serpentine animal, although it remains open whether it is being warded off or drawn towards her. The bald head refers to the feeling of defenselessness and vulnerability.

Ambivalent emotions are also the theme of Hermann Albert’s painting “Sich kämmender Akt”. A naked woman seems to feel unobserved in her room. But a shadow on the wall reveals a male observer. The threatening aspect of desire and love is illustrated. At the same time, the scene is also a statement on the subject of voyeurism in male-dominated art, in which the long artistic tradition of depictions of female nudity manifests itself.

Encounters

At first glance, Markus Lüpertz’s painting “Zwei Krieger” appears threatening. Two figures with archaic shields, sword and lance meet each other aggressively. Their faces, however, are covered with masks that appear rather amicable and open. The scene thus conveys an impression of the diversity of male adversaries, oscillating between curiosity and aggressiveness.

The bronze sculpture “Wanderer namenlos” by Sylvia Hagen presents three sketchily modelled figures. The main focus is on the stances of the bodies, which are turned towards or away from each other. The interplay of closeness and distance is inscribed in the “wanderers” on the path of life.

Gerhard Altenbourg’s woodcuts work with the serial reproduction of a figure that is always the same. Lined up one after the other, they convey the uniformity of the anonymous mass of people. At the same time, the colourful design and the printed grain of the wood give rise to reflection on the simultaneous uniqueness of the individual.

Altenbourg’s filigree drawing “Flug” shows a single being, a mythical-mystical figure with wings, separated from its surroundings by the ability to fly. The head turned with a gentle smile, however, seems to indicate the existence of others.

Life in the city

Among the early works from the collection are Werner Heldt’s charcoal drawings from Berlin. Here he observes scenes from post-war everyday city life, depicting gatherings of people as they often occurred in urban life at the end of the 1940s. In these depictions, the individual formally merges with the mass.

In Thomas Hornemann’s “Cabaret la Marina” and Kurt Mühlenhaupt’s “Sommerlicher Badestrand”, the cheerful side of city life is illuminated. People get close to each other during leisure activities ranging from dancing in the pub to sunbathing, bathing and playing on the beach.

The confusion of the big city is the theme of Ulla Walter’s work “U-Bahn”. The human figures are dissolved into abstracted forms, yet the feeling of crowdedness, confusion and density is visible. The individual does not appear on the train, but is lost in the tangle of the masses.

Silke Miche’s “Kästen” does not show people themselves, but their urban living situation. In the seemingly endless row of balconies, the conformity and narrowness of urban living space becomes clear. The bright colours, however, dissolve the oppressiveness and hint at the individuality of the residents.

A look back

With the political turnaround after 1989, a fundamental political and social change occurred in German history, which found artistic expression in subtle ways.

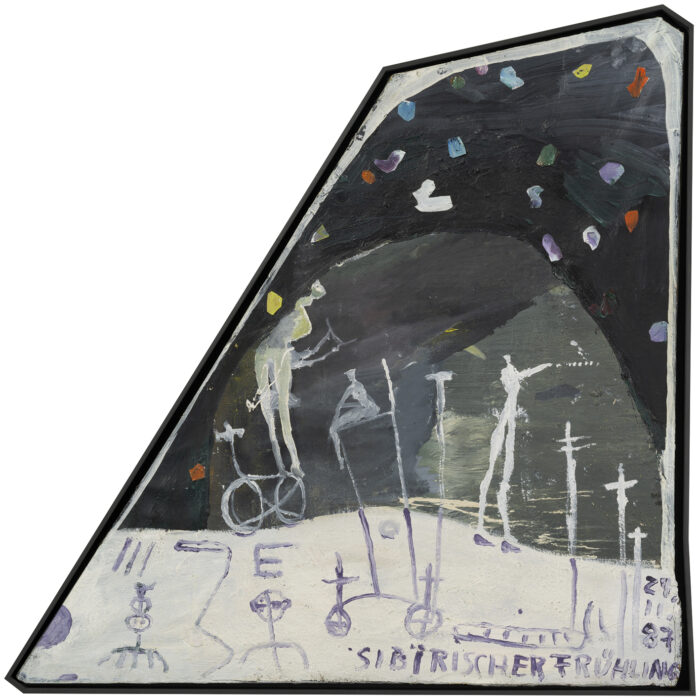

In the painting “Sibirischer Frühling,” Cornelia Schleime illuminated her personal situation when she left for West Germany in 1984 after great pressure from the GDR authorities. The painting shows a snow-covered landscape, a distant “Siberia” from which she was now able to distance herself. The colourful dots as well as the “Frühling” (spring) implied in the title symbolise her optimistic mood of departure.

Wolfgang Peuker’s 1990 painting “Pariser Platz II” is quite different. A leaden grey impenetrability dominates around the Brandenburg Gate. Although the gate has been opened by the fall of the Wall, the world beyond the gate seems infinitely distant. One intuitively tries to avoid an encounter with the eerie dark figures that come from there.

Harald Metzke’s “Blinde Kuh” is also ambivalent, a painting that at first glance seems to be depicting a cheerful party game. Yet, as is so often the case with Metzke, the painting can also be understood as a metaphor for social interaction. The blindfolded woman is trying to touch the other people. She is trying to make contact with them. If one considers the genesis of the work in the German post-reunification period, it could also be a commentary on the encounter between East and West Germans. The not-seeing with blindfolded eyes is symbolic of the not-knowing and not-understanding in the attempt to come together – and the evasive fellow players also underline the failure of the encounter.

Janina Dahlmanns

The presentation at the Kunstforum der Berliner Volksbank showed how the 1920s era has influenced the artistic work of later generations up to the present day.

The 1920s still fascinate people a hundred years after this exciting epoch. This is reflected in the success of series such as “Babylon Berlin,” but also impressively in the fields of design, modern literature and current fashion.

Art reacted to the 1920s in its own time with styles such as New Objectivity and Magic Realism. The exhibition “Die wilden 20er – Nach(t)leben einer Epoche.” (The Wild Twenties – The Afterlife of an Era) shows the extent to which later generations of artists were inspired by these styles and still are today. The exhibition shows works by Gudrun Brüne, Albrecht Gehse, Hubertus Giebe, Otto Gleichmann, Clemens Gröszer, Karl Lagerfeld, Hartmut Neumann, Roland Nicolaus, Wolfgang Peuker, Bernard Schultze, Volker Stelzmann, Christian Thoelke and Britta von Willert are presented.

The artworks were created from the 1970s to the present. They bear witness to how influential this epoch was in terms of style, and that later generations of artists also made reference to the clear, austere representationalism of New Objectivity and the surreal and alienated scenes of Magic Realism.

A catalogue has been published to accompany the exhibition and is available for purchase: Publications

Catalogue text by curator Dr. Janina Dahlmanns

The Berliner Volksbank art collection focuses on representational art, which was mainly created in Berlin and the surrounding regions after 1945. The collection, therefore, contains the most diverse range of positions in German modernist art, from expressive forms of expression to old-masterly realist painting to strikingly reduced viewpoints. One group of works stands out for its precise, almost emphatically realistic painting style as well as its naturalistic rendering of colours, volumes and perspective. At the same time, they show alienating effects such as lighting conditions reminiscent of nocturnal visions or dreams, or exaggeratedly dramatic gestures. Some paintings are permeated by a mysterious atmosphere and encourage the viewer to consider the particular mood in each case.

The earliest paintings of this kind from the Berliner Volksbank art collection were created in the 1970s, such as “Nachtcafé” by Hubertus Giebe. A whole series, on the other hand, dates from the last 20 years, such as the works by Clemens Gröszer, Volker Stelzmann, Wolfgang Peuker or Gudrun Brüne. The painting style of these artists is reminiscent of the overly precise style of verism of the 1920s.

During the Weimar Republic, currents that were more strongly oriented towards seen reality, such as Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) or Magical Realism, became increasingly prevalent in German art. After modernism had broken with traditional forms of representation around 1900 – Impressionism with the idea of uniform light, Expressionism with naturalistic colouring or Cubism with classical perspective – a “return to order” was evident in art throughout Europe. After the horrors of the First World War, artists in Germany strove for a new objectivity and an unsparing depiction of what they saw. The uncovering and criticism of social ills and societal ambivalences were to be visualised in this way. Other artists painted scenes that only appeared realistic at first glance, but on closer inspection revealed breaks with familiar reality and made the uncertainties of the social situation visible. A lively and thoroughly diverse art scene illustrated the 1920s. From the boisterous celebrations of the bohemians in the cities and their dance on the volcano to the new understanding of the role of the modern woman to the enormous social problems and the gap between rich and poor, everything was thematised. This short era came to a brutal end when the National Socialists came to power in 1933, bringing this cultural flowering to an abrupt end.

The question arises as to why artists such as Clemens Gröszer, Volker Stelzmann, Hubertus Giebe, Wolfgang Peuker or Gudrun Brüne reacted so forcefully to the style and themes of this period many decades later.

By the mid-1960s, a first renaissance of the visual language of the 1920s had already emerged in the eastern part of Germany. At the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig, a figurative art movement emerged that broke through the narrow guidelines of the “Socialist Realism” prescribed by the state and revived the painterly, technical refinements of various art historical models. The so-called “Leipzig School,” still famous today, was born. Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer and Bernhard Heisig also took their cue from greats of the 1920s such as Otto Dix, Giorgio de Chirico, Oskar Kokoschka and Max Beckmann. In Tübke’s work, the examination of older art, especially Renaissance and Mannerism, played a major role. The artists of the 1920s had already turned this gaze to the past. In a sense, one can speak stylistically and technically of the renaissance of a renaissance, which was, however, thematically related in each case to the current present. The art of the “Leipzig School” established itself through its three main protagonists and was carried on and developed by its numerous students at the Leipzig Hochschule. Two stylistic currents dominated: painting in a veristic, precise glaze technique and painting in a gestural, impulsively designed pastosity.

In the 1970s, Giebe, Stelzmann and Peuker studied at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst. They found models for their own artistic work in the examination of Otto Dixs’ work, but also of Giorgio de Chirico, a representative of the Italian Pittura Metafisica, which developed parallel to Magical Realism in Germany. For Giebe, Max Beckmann was an exciting inspiration, Stelzmann dealt with even older masters of art history such as El Greco or Pontormo, while Peuker developed his own variety of Magic Realism. Each of the artists thus arrived at a very personal style.

Thus the art of the Leipzigers succeeded in the balancing act of, on the one hand, ostensibly conforming to the desired line of GDR art policy, setting itself apart from the West through representationalism, and thus enabling itself to work artistically in a more or less undisturbed manner – on the other hand, possibilities opened up for making its own and independent pictorial statements, precisely through alienation and profundity. Thus, the direction of Magic Realism, which originated in the 1920s, offered many artists in the GDR an approach of using enigmatic elements and numerous layers of meaning to refer to the pictorial statement that was actually relevant to the artist – only that this was not apparent at a superficial glance.

Common characteristics of the artists such as Giebe, Stelzmann and Peuker are the precise lines, the attention to detail and the finely glazed layers of paint as well as the surreal and magically charged subjects. Moreover, they have maintained their respective individual styles even during the Wende and post-Wende periods. It seems that the visual language they found was suitable for vividly depicting their own feelings even in the face of social and personal changes.

Other examples of artists who transferred this style of painting, which borrowed from the art of the 1920s, into their handwriting are Gudrun Brüne, who trained in Leipzig and then worked as a lecturer at Burg Giebichenstein in Halle, and the two Berlin painters Clemens Gröszer and Roland Nicolaus.

Gröszer often created complex narratives with his works, using multi-layered references from all eras to create a conundrum of human longings, dreams, hopes and expectations. He incorporated allegories and symbols into his works, interweaving the worlds of dream and fantasy with elements from his everyday life. Thus his figures, who reside in mysterious shadow worlds, are dressed in the chic of the contemporary underground scene, while a masked magician may be standing next to the S-Bahn station at Berlin’s Alexanderplatz. Gröszer transposes an ancient way of painting into his present, while the technical perfection of painting was also always a major concern.

“Early on, Gröszer belonged to the group of painters who attempted to rescue genuine painterly ideas from the ingredients of the crisis, the loss of autonomy, media competition and the new, commercially determined cultural sign system, so to speak.” (Matthias Flügge, in cat. Gröszer – Antlitz, 2012, p. 11)

Gudrun Brüne’s work also focused on painterly precision, while at the same time her work is permeated with symbols and allegories of human existence. Her work often mixes genres: Portraits are combined with still lifes and figures enter into silent dialogues with things. Dream and memory images are merged with real scenes from Bruene’s studio. The objects, such as dolls, masks, mementoes, play a symbolic role that underlines the overall effect: the outside world is reflected in the inside world of the studio.

Roland Nicolaus deals with the 1920s in a special way. In his most recent works, he combines various painterly styles, from meticulous detail painting to bold Pop Art, and creates collage-like panoramas. This is also a conscious reference to the 1920s since the principle of collage first emerged in this period with the Dada movement. In these painted collages, sometimes supplemented by pasted-in evidence of everyday culture, Nicolaus picks up on figures, observations and phenomena of social reality in Berlin in the 21st century and presents a moral image of the present. Through quotations from art history in constellations and figures, he reveals distortions and absurdities of the social reality of the present, in which he certainly sees parallels to the 1920s in Germany in terms of content. The result is a bitterly wicked commentary on the present situation.

This magical-surreal direction in the art of the late 20th century, which forms a significant part of representational art in Germany, does not, however, find an endpoint with the generation of artists trained in the GDR. The fascination with painterly accuracy, the detailed formulation of the superficially visible in connection with subtly hidden levels of meaning is continued into the present by younger generations of artists.

Britta von Willert, for example, who trained in the early 2000s, has also opted for representational painting, modelling figures and spaces with realistic precision. At times, she incorporates conceptual images into the depictions and shows an openly conceived tradition of the magical-surreal, as in her series of Berlin paintings, which make the place’s known past visible in figures taken from historical black-and-white photographs of the early 20th century and create suspenseful cross-fades. In other works from Berlin’s nightlife, the quiet atmosphere and introverted figures recall the depictions of the American painter Edward Hopper. In the 1920s and 1930s, Hopper visualised the loneliness of modern man and the alienation of city life.

Depicting the social issues of the present in the relationship to human emotions is also the aim of Christian Thoelke, who studied in the years before and after the turn of the millennium. His paintings are dominated by what at first sight appears to be a calm mood, but on closer inspection is also perceived as latently sinister and charged with tension. It is about universal questions of man in relation to upheavals, uprooting, transitions, fears and longings. The social themes are not depicted narratively but made visible in their essence and core. The painterly sharpness of detail and precision in Thoelke’s painting is reminiscent of New Objectivity – but it also betrays the inspiration and stimulation of his teachers Wolfgang Peuker and Ulrich Hachulla, both of whom carried on the technical care of the “Leipzig School.”

The art of the 1920s thus continues to have an effect today and inspires generations of artists. Their approach and style offer a possibility to transfer the questions and observations of one’s own reality of life to art, independent of contemporary styles and fashions. The accuracy of the technical realisation goes beyond subjective ego-feeling and the expression of personal sensitivities. The precise description of things as well as the mysterious enigma and great atmospheric tension make it possible to visualise thoughts on the social situation without appearing narrational and striking. Instead, the viewer’s thought process is stimulated in a subtle way and his attention is challenged for nuances and intermediate tones. This is what makes this style of figurative art so appealing and fascinating, a style that, in a way, is timeless and endures into the Post-Post-Modern era.

Janina Dahlmanns